The Loves I Have Known: In Conversation with Louise Mandumbwa

Louise Mandumbwa contends with her diasporic experience in her multimedia practice. Lara Xenia speaks with the artist about her botanical research, material exploration, and intergenerational knowledge.

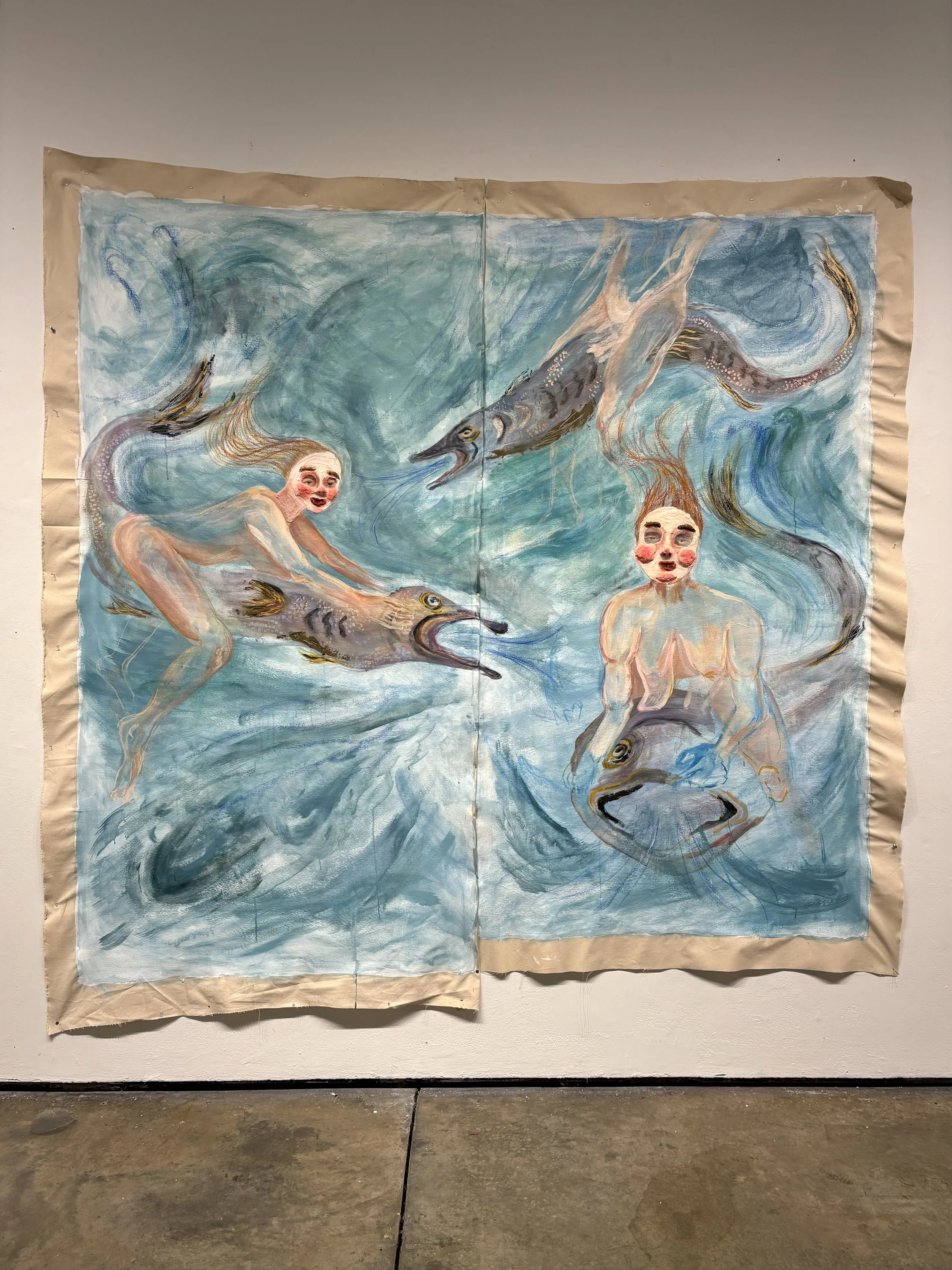

Figure 1: Installation view of The Loves I Have Known, 2025, paper, canvas, graphite, ink and charcoal, 60 x 46.5 inches (152.4 x 118.11 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

Lara Xenia: What was the first piece of art you've ever stared at?

Louise Mandumbwa: I grew up in a really small town that didn't have big cultural museums or institutions, so a lot of my first interactions with artworks were through ones I’d find online or in the pages of books. It wasn't until I was a young adult, like 18 or 19, that I experienced one of those seminal works in person. In the Crystal Bridges Museum in Northwest Arkansas, I turned the corner in the contemporary wing and was met by a Barkley Hendricks painting. Four figures in white, and a lady that had a little afro. It was an image I'd revisited often. Seeing it in person stopped me in my tracks as a work I had been struck by as a younger person, now directly in front of me.

Figure 2: Barkley Hendricks, What’s Going On, 1974, oil, acrylic, and magna on cotton canvas, 65 ¾ x 83 ¾ inches (167 x 212.7 cm). Photo: courtesy the Estate of Barkley Hendricks

LX: I love Hendricks. Was that the first time you went to a museum here? How did it compare to the museums and art spaces you had access to before?

LM: It was. I came to the U.S. specifically for my higher education when I was 18, and was fortunate that I had the opportunity to visit major art institutions in my few years here. Prior, I had spent most of my years in Francistown, Botswana. It was a sweet, nondescript town, which I called home. What Francistown didn’t have in abundance, however, was a robust collection of formal art institutions.

LX: Is that partially what incentivized you to study here in the States?

LM: Oh definitely. I set my sights on art school in the U.S. at 18. I dreamt of attending SCAD, but I soon learned that scholarships for international students were scarce. Family friends in Arkansas offered guidance and a home near a local community college. Thanks to their generosity, I came here and earned an Associate’s degree in Graphic Design. I later transferred to the University of Central Arkansas, where I completed a BFA in Painting and discovered printmaking. It profoundly transformed the way I think about process, repetition, and material. After graduating, I interned at a gallery, then moved to Virginia to focus on my portfolio and graduate school applications. I was accepted into my dream program, moved to New Haven in 2022, and graduated in 2024. Each stage of that path continues to shape the way I approach my work.

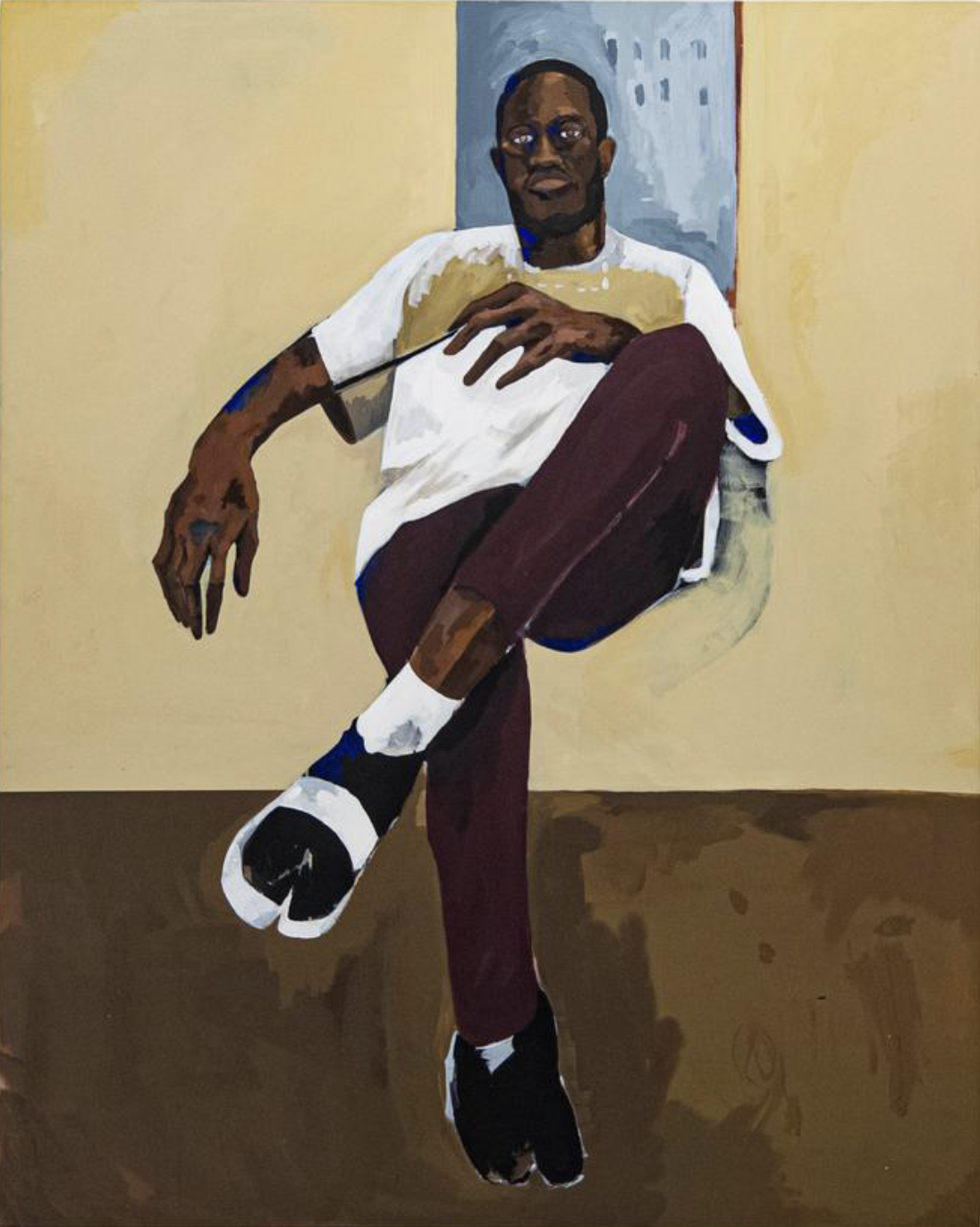

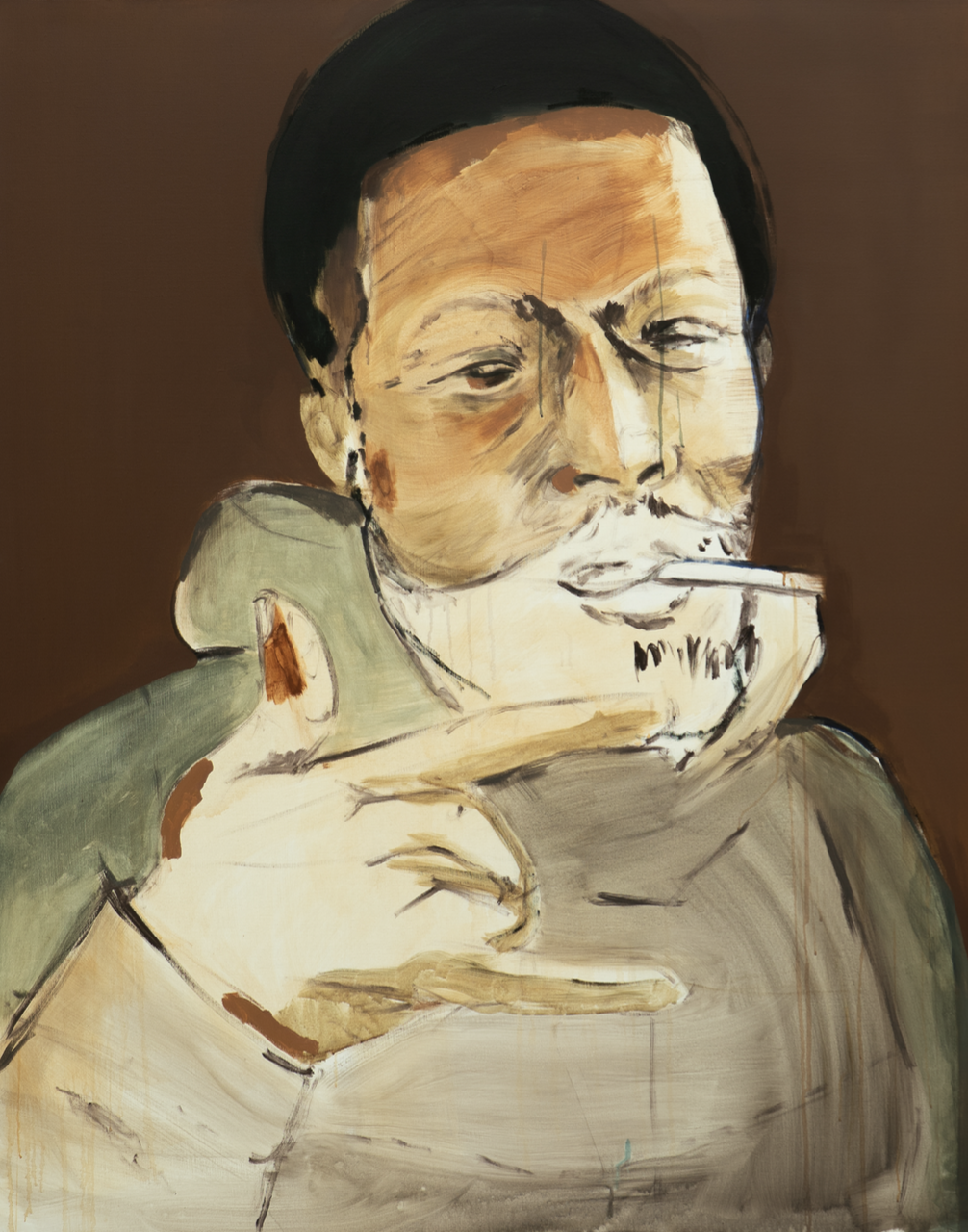

LX: Your portraits are stunningly detailed, and it’s quite a departure from your recent body of work. Where is it situated in your practice?

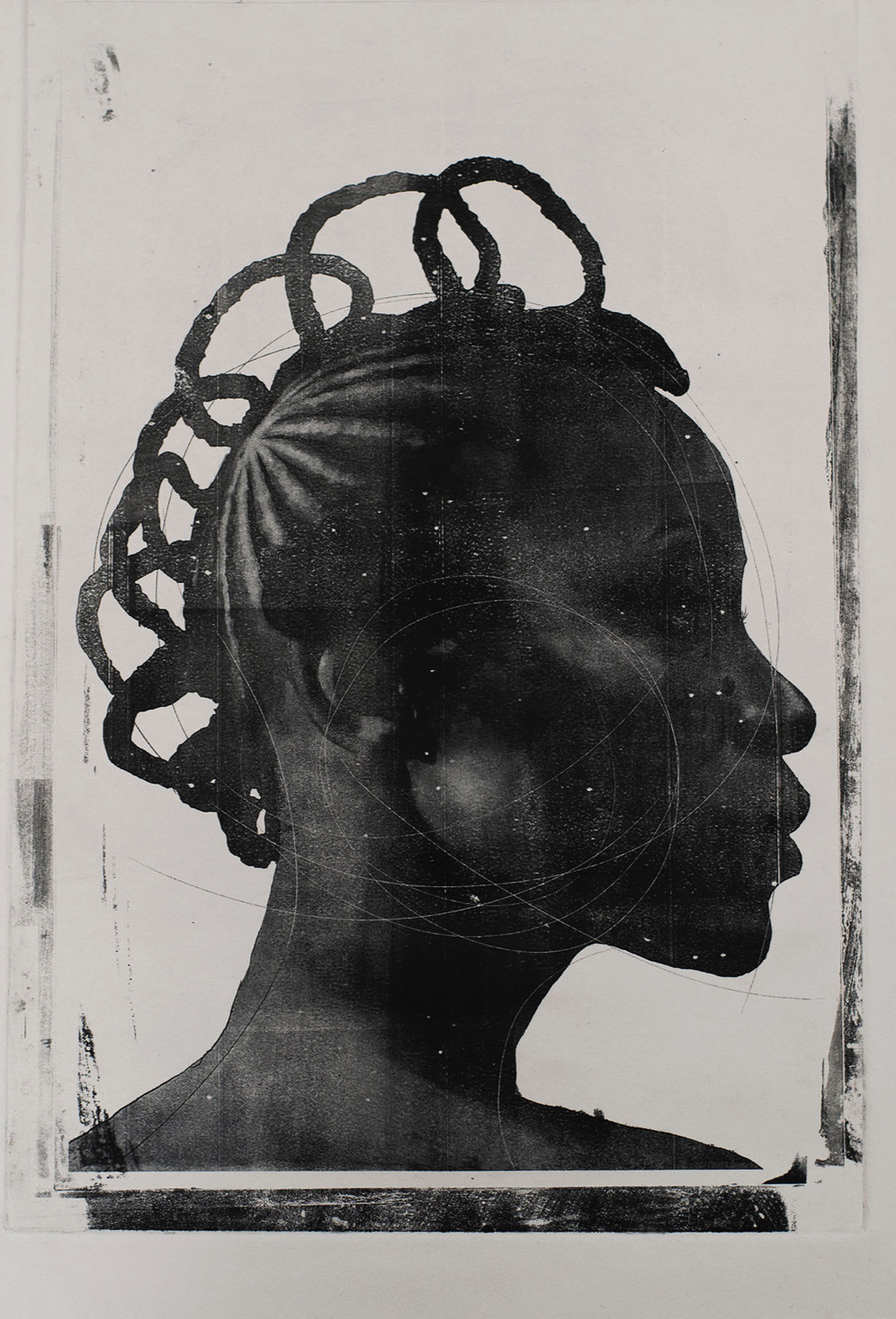

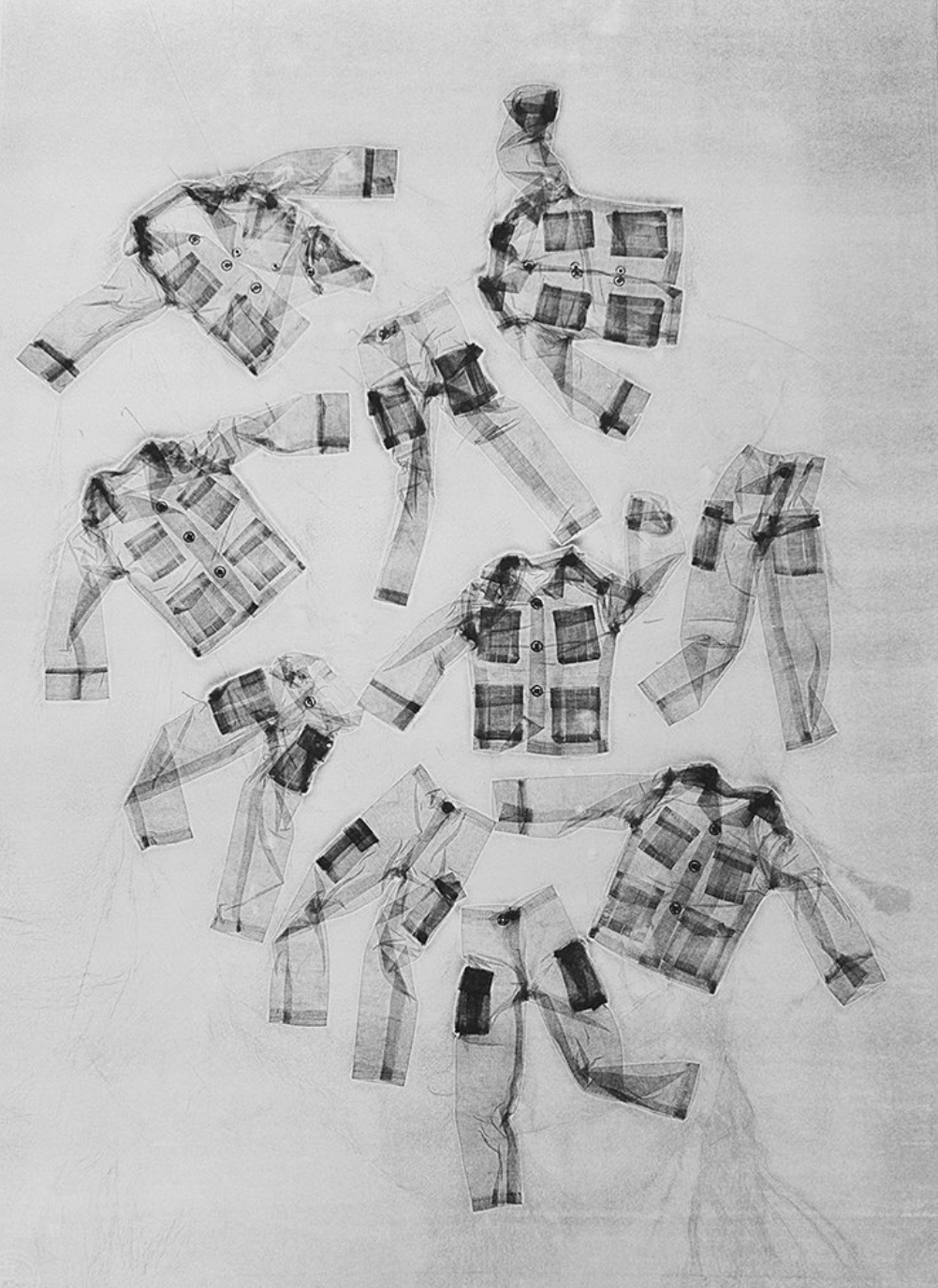

Figure 3: Louise Mandumbwa, Good Immigrant, proto plate print, 2019, 17 x 11 inches (43.18 x 27.94 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

LM: My early practice was focused on technical execution. Being too shy to ask others to sit for me, I turned to the work of photographers I felt were making compelling work, using some of those images as references for pieces that helped me refine my visual voice. The muse for this work was a South African artist, Kwena Baloyi. Throughout that exploration I progressively became interested in how ranging mediums handled control, chance, and repetition differently. Painting always offered a sense of precision and intention, and printmaking refused that control. The unpredictability of the process revealed something I couldn’t achieve through painting alone.

I discovered pronto plate lithography, which uses polyester sheets instead of stone. Unlike traditional litho, the plate deteriorates quickly, producing only a few prints before the image begins to break down. Each pull erases a little more information. That material decay and erosion became a metaphor for memory itself and its unpredictability in fading. We don’t choose what we forget, and we rarely notice when the image begins to disappear. This process allowed me to explore absence and loss not as failures but as forms of meaning, when what is missing carries as much weight as what remains.

In many ways it was through the discoveries of this process that my work began to focus more on memory and a perspective shaped by my experience as the daughter, and granddaughter of immigrants. When I started photographing people close to me, I realized that the totality I sought in painting did not align with how memory actually works. I was aware of gaps in my own family history; how stories were half-told or lost. Memory, at least as I’ve experienced it, is often fleeting, fragmentary and pieced together to make up an approximation.

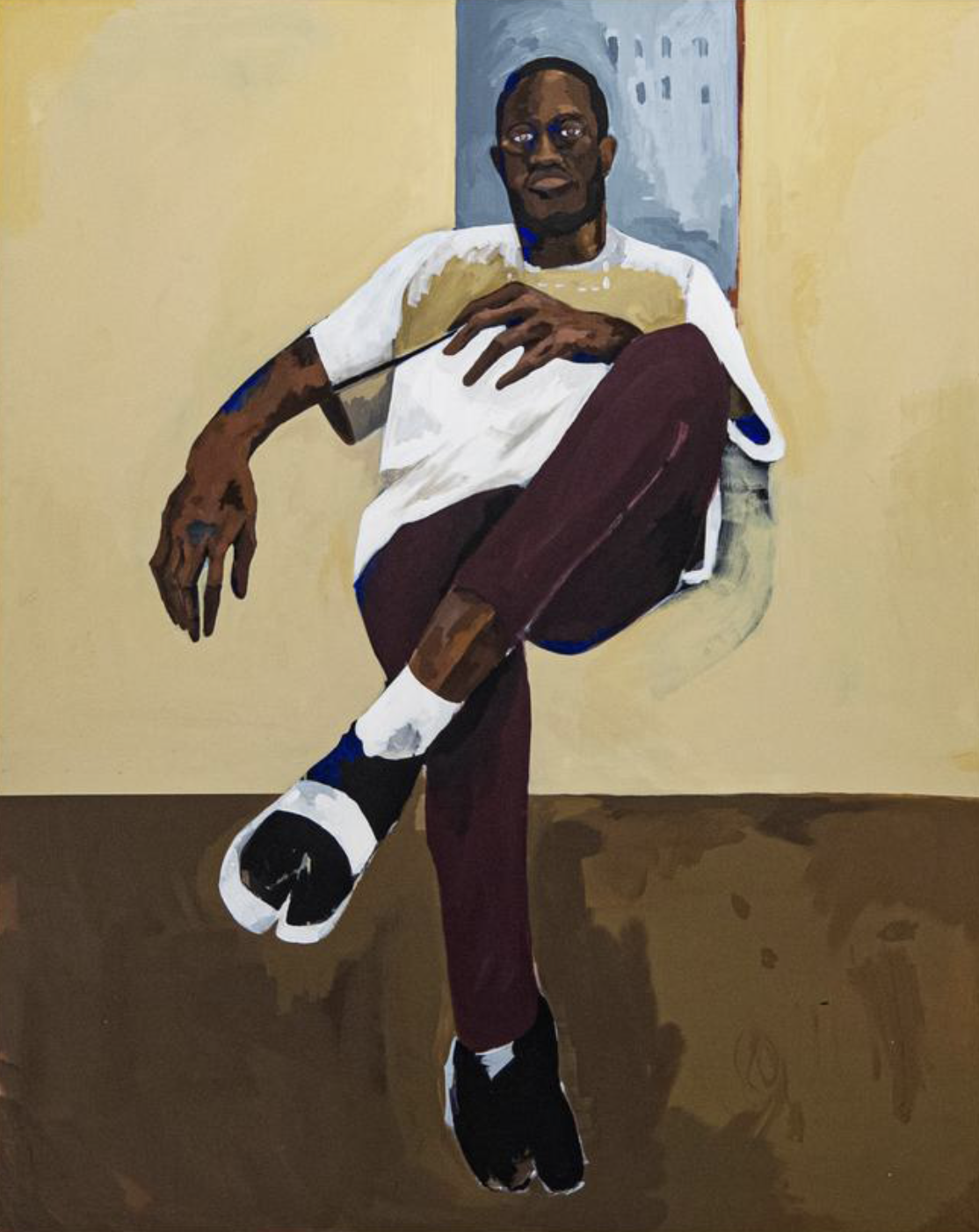

LX: I’m especially drawn to the multi-faceted, trace-like elements in your work. Were the figures in your portraits based on people you were personally connected with at the time?

LM: Absolutely. People often asked where I was from when I first moved to the U.S. and I noticed that my answers were never about geography or infrastructure, but about the people I knew. I understood places through the people who shaped them for me. In my early work, around 18 or 19, I began painting portraits based on photographs I had taken myself. Each work was tied to a personal story.

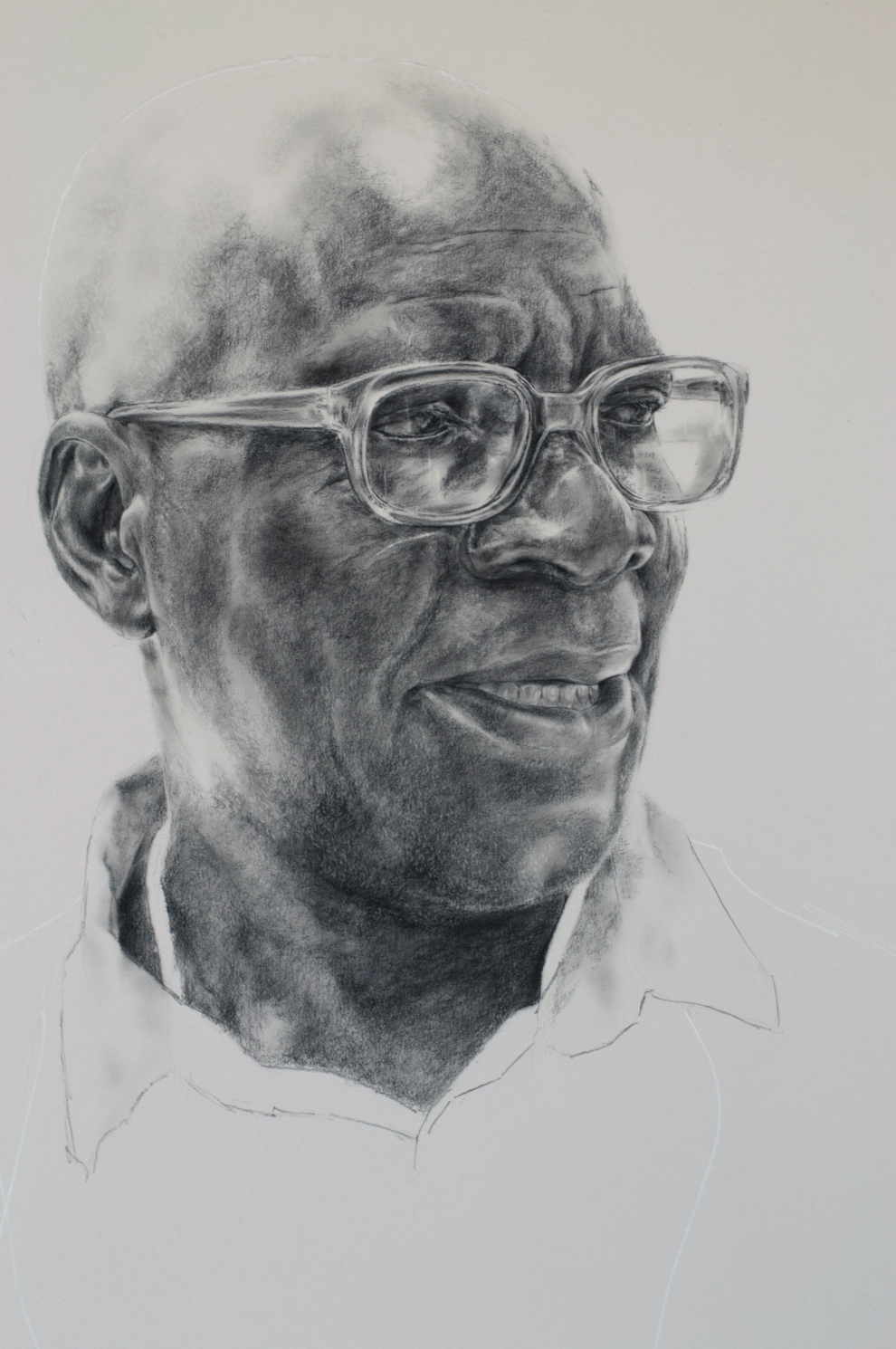

Figure 4: Louise Mandumbwa, Jacob, 2021, charcoal on paper, 30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.88 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

Figure 5: Louise Mandumbwa, Rre Dodzi, 2021, charcoal on paper, 30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.88 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

One portrait shows Jacob, the security guard at my high school, who greeted me every morning for six years, and another depicts an older man named Rre Dodzi or Mr. Dodzi, who watched me grow up in my childhood neighborhood. Those early portraits became an archive of belonging, and a way to map my home through human connection. I have never had a strong recall for faces, but through painting and drawing, I found that I remembered them more clearly. These drawings became a way to commit their presence to memory and to show people where I’m from.

LX: Fascinating. What led you to pursue making works about sugarcane?

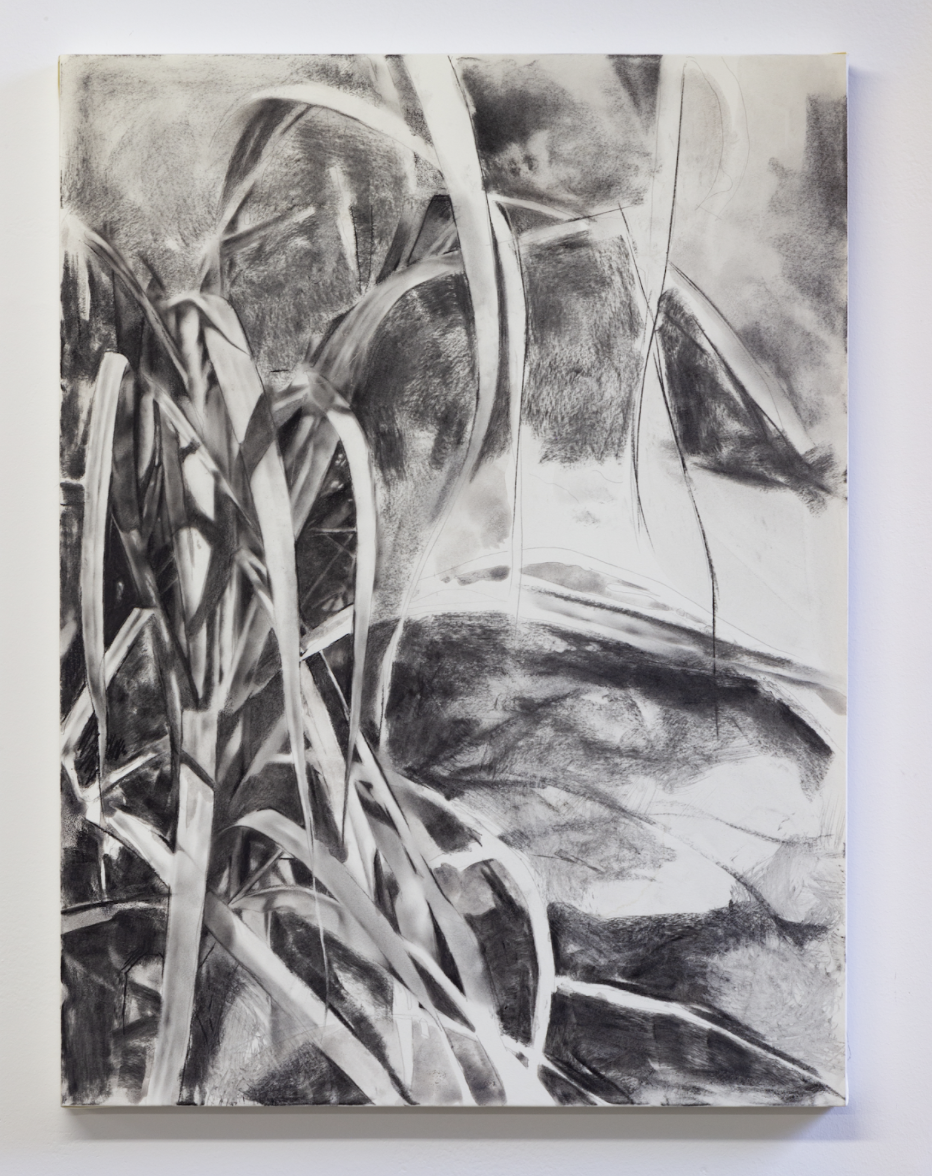

Figure 6: Installation view of They stole the sweet away, 2023, charcoal on paper; 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia

Figure 7: Configuration 1, 2023, paper, canvas, acrylic, and charcoal, 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm); 36 x 12 inches (91.44 x 30.48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Zeshan Ahmed

LM: In grad school, I began rethinking how I mapped relationships. I’d always understood “places” through the relational, but wanted to make touch points that allow others to enter the work without needing my full personal history. That led me to think about the gardens I grew up around, like my grandmother’s home, which had sugarcane, guavas, and plants that she’d tend to. I began to see gardens as parallels to relationships; always in flux or nurtured and maintained overtime. My grandmother’s and mother’s gardens were constantly changing, but certain trees remained, and reflected their degree of care.

Those early portraits became an archive of belonging, and a way to map my home through human connection.

Figure 8: Installation view of Configuration 1C, 2023, paper, canvas and charcoal, 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm); 36 x 12 inches (91.44 x 30.48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia

When I no longer had access to the people who shaped those memories, I found a similar sense of connection in plants that existed elsewhere. Sugarcane grows in many regions, as does yucca or cassava. Encountering them revealed how plants also trace histories of movement. I learned that cassava, which I had always associated with the Congo where my grandmother grew up, was introduced there by the Portuguese because of its resilience to drought. I was fascinated by how plants like cassava and Bougainvillea appeared across continents, and quietly mapped diasporic movement. Their presence is not about invasion, but about contact, exchange, and transformation. These plants hold the intertwined histories of place, migration, and adaption, much like the people who care for them.

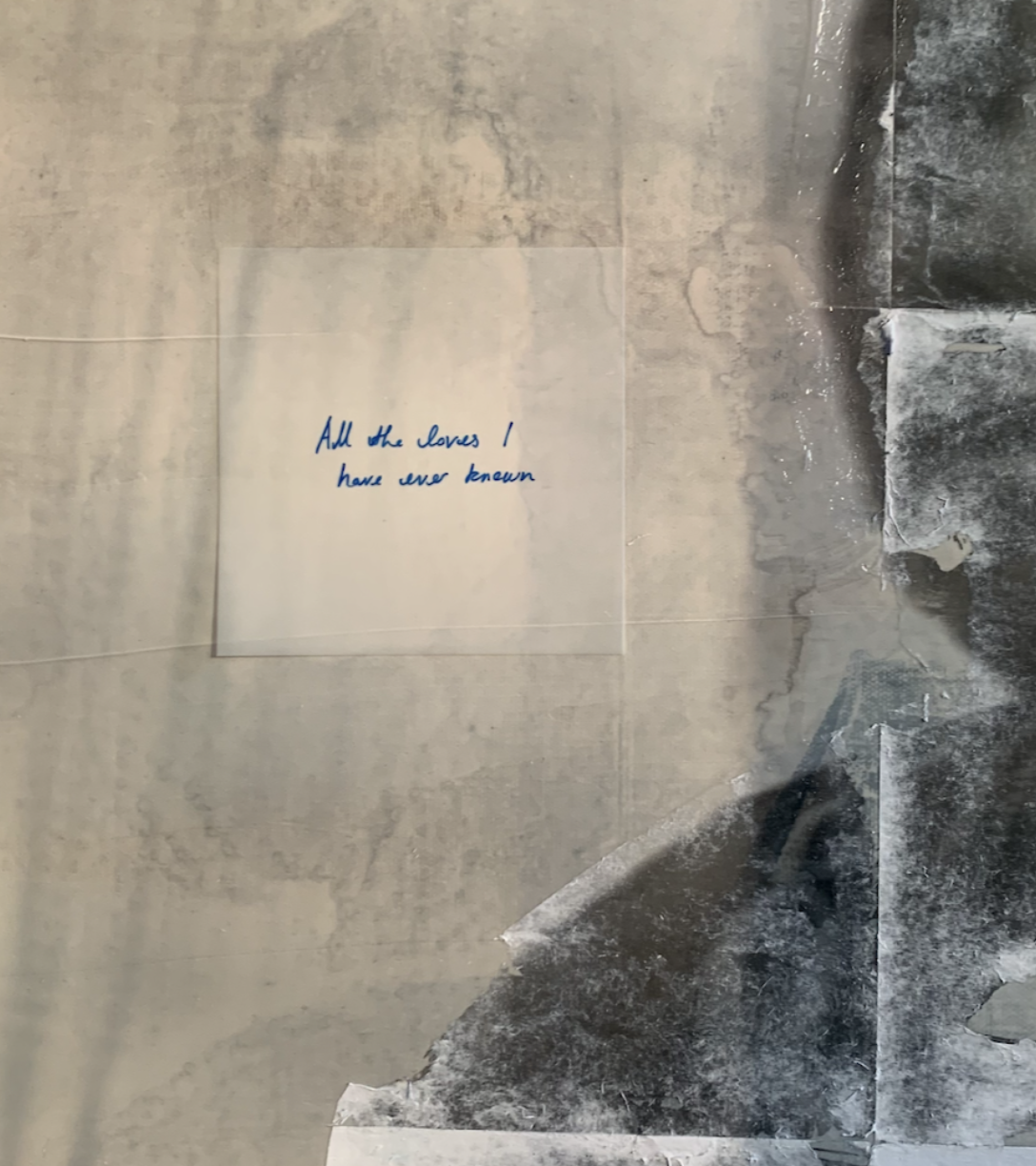

LX: That's so interesting. Do you usually combine yucca with other plants in these works? What inspired you to layer these elements, and what is the text embedded above it?

LM: Much of the text begins as annotations made directly on my paintings and drawings. I used to write on the surface itself, then copy the text into a field journal before erasing it. The writing often takes the form of short poetics and fragments that respond to what I’m thinking about while I work. Now, I write on transparent sticky notes that I place in my journal. The clear paper mirrors the studio process, and layers text and image in a way that feels both visible and ephemeral. The fragmentation in my work grew out of realizing that I was trying to capture something total in a painting and always falling short. I began to see that failure as more honest. Memory itself is partial; some things are recalled through language, and others are through image, color, or material association. By bringing those fragments together, like what can be named clearly, what can only be felt, I try to create a visual language that reflects how memory actually lives in the body. It is less about precision and more about assembling what remains, by allowing language, image, and material to speak to one another.

Figure 9: Untitled [detail], 2023, paper, canvas and charcoal, liquid graphite, 36 x 30 inches (91.44 x 76.2 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist

LX: I’m interested in how you fragment elements across the canvas and combine different surfaces within one composition like wood or other supports. The variation in surface gives the work a tactility, and its own rhythm and weight.

LM: Materially, I was thinking about home, and what it means when it’s not a physical structure. I had been challenged that my work rarely depicted an interior space, as something that could be visually read as “home.” I resisted that, because I believe you can be dispossessed of a building in a way you cannot be dispossessed of a relationship. I began to explore how material could point toward that idea. I used concrete, wood, glass, and eventually Plexiglas, which would not shatter. I also worked with aluminium and steel, which are used to construct homes in Zambia, Botswana, and much of Sub-Saharan Africa. I wanted to bring that vocabulary of materials into my work, even if the image itself did not depict a house. For me, these materials carry the presence of home through its material vocabulary, with its texture, resilience, and weight, even when the form itself is absent.

Their presence is not about invasion, but about contact, exchange, and transformation. These plants hold the intertwined histories of place, migration, and adaption, much like the people who care for them.

Figure 8: Louise Mandumbwa, Configuration 1, 2023, paper, canvas, concrete, plexiglass, acrylic, gouache and charcoal, 12 x 12 inches (30.48 x 30.48 cm); 22.5 x 19 inches (57.15 x 48.26 cm); 16 x 6 inches (40.64 x 15.24 cm); 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm); 36 x 12 inches (91.44 x 30.48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia

LX: I’m really interested in how you fragment the composition and layer the plants in the foreground then echo their remnants in the background, as if they exist in another space. You also use yellow often. Is that hue somehow reminiscent of home for you or does it carry a particular connection for you?

I try to create a visual language that reflects how memory actually lives in the body.

LM: That’s exactly it! I had been writing about what home might feel like, look like if it had a color, a taste, or a texture. I wanted to think more critically about my relationship with color, rather than just working from photographs. In my notes, I wrote about the time of day when I would come home and stand in my mother’s garden. I would close my eyes and feel the light shifting as the sun set. Because we lived near the tropics, the sunsets were long and warm, and filled with yellows and oranges that seemed to filter through my eyelids. When I think of home, that light is what returns to me. If home had a color, it would be that warm, glowing yellow that lingers just before dusk.

LX: It’s cool that you vary the scale and height of the works. It definitely changes how the viewer relates to them and walks through space.

LM: Yes, and with the botanical pieces, I’m interested in placing them at the height of their real world referent, swaying overhead, or close to the ground. It’s not a literal replication, but I want viewers to experience the work in the spatial register where it exists in nature.

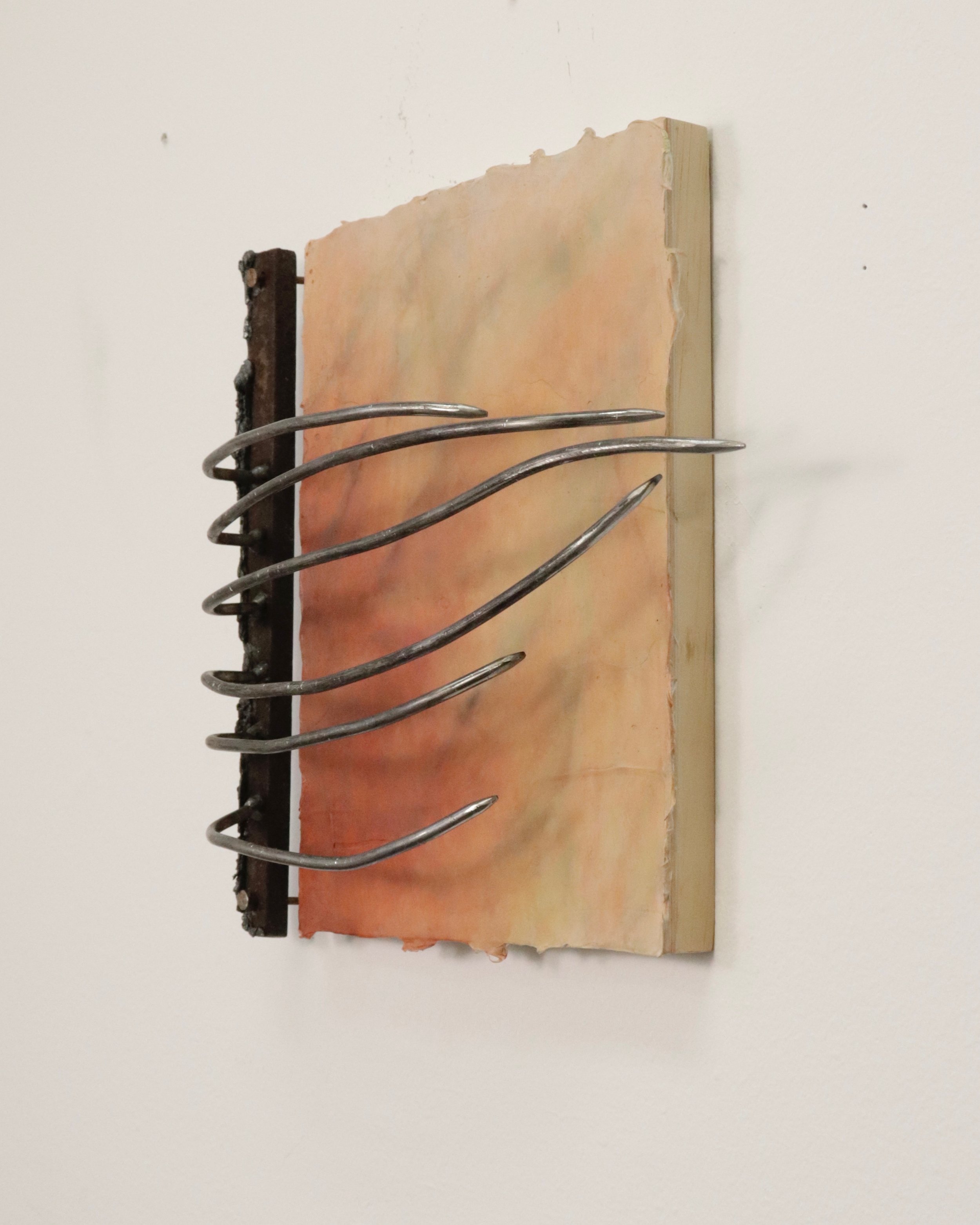

Figure 11: Louise Mandumbwa, Something to Hold Onto, 2024, cast aluminum and carborundum, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Louise Mandumbwa

Figure 12: Louise Mandumbwa, Something to Hold Onto, 2024, cast aluminum and carborundum, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Louise Mandumbwa

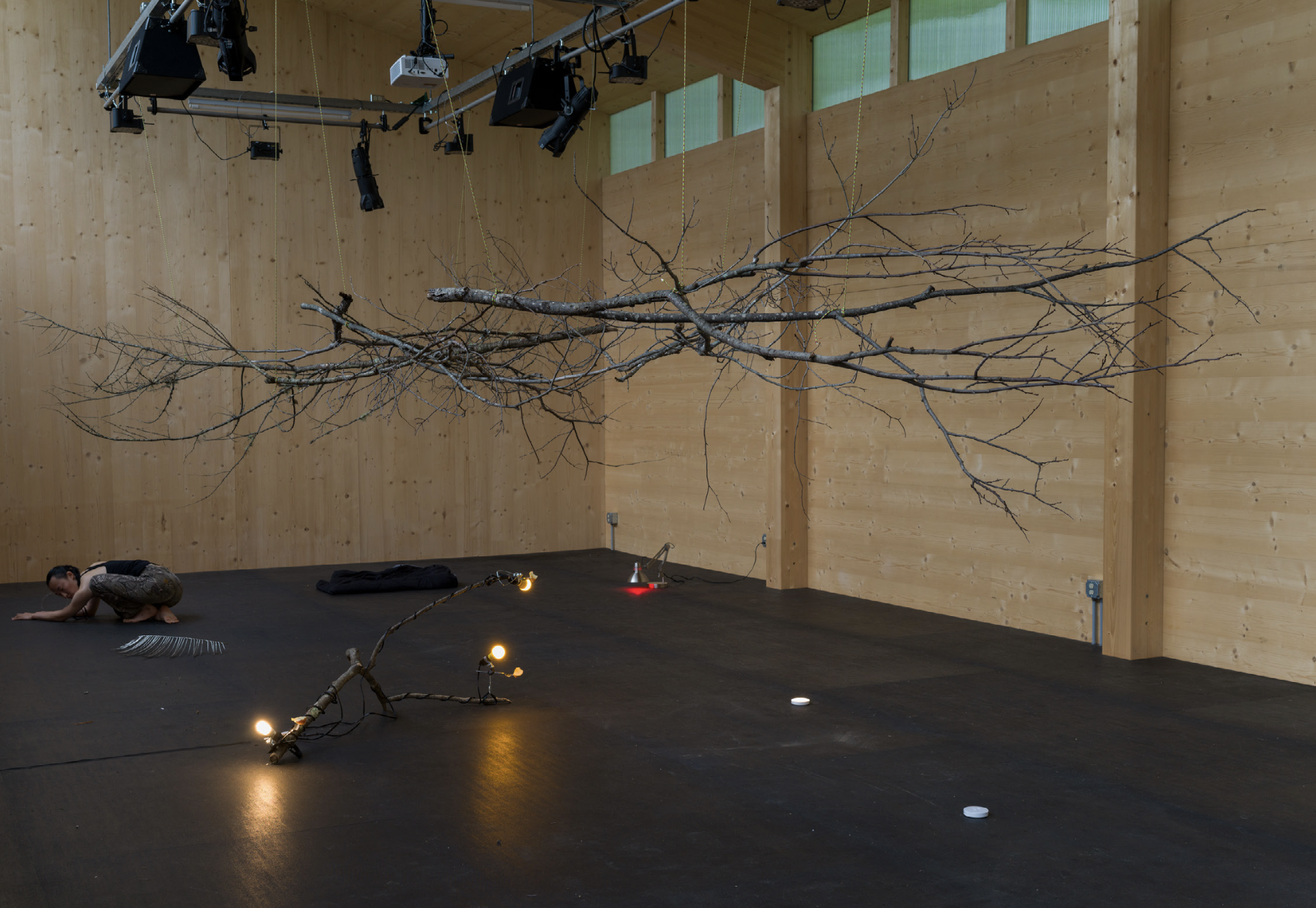

LX: I also wanted to ask about these barren tree-like forms. Is that actual soil in the piece, or a material meant to emulate it?

LM: It is meant to emulate soil. The material itself is carborundum, which in printmaking is used to reset a lithographic stone by removing an image. It has a texture similar to sandpaper in powdered form. I was drawn to it because it holds a kind of material memory, shifting an image from something perceivable back to pure matter. The sticks are cast aluminium. Between my first and second year of graduate school, I visited my father's hometown near the Angolan border in northern Zambia, Chavuma, a place I had never been before. What struck me most was the prevalence of yucca, a plant I had always associated with my grandmother and with the Congo. My family’s roots extend into Angola as well, and yucca is part of daily life there. Because I was already making drawings of plants, I began to imagine an archival garden. I collected cuttings of yucca from my grandmother’s home, casting them in aluminium, and created the first iteration of what I hope will grow into a more expansive living archive.

LX: That’s beautiful. How did this one come about? [Gestures to painting]

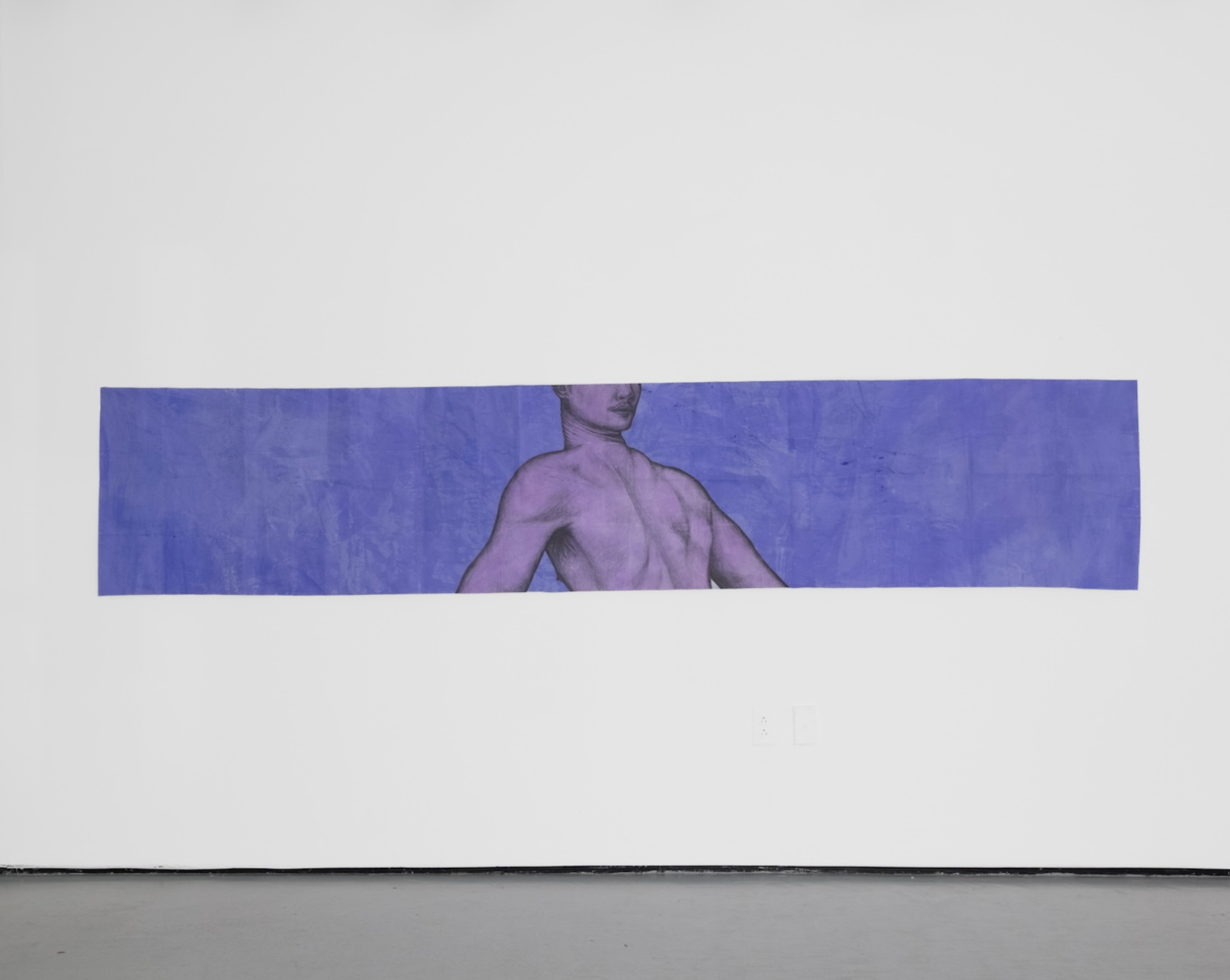

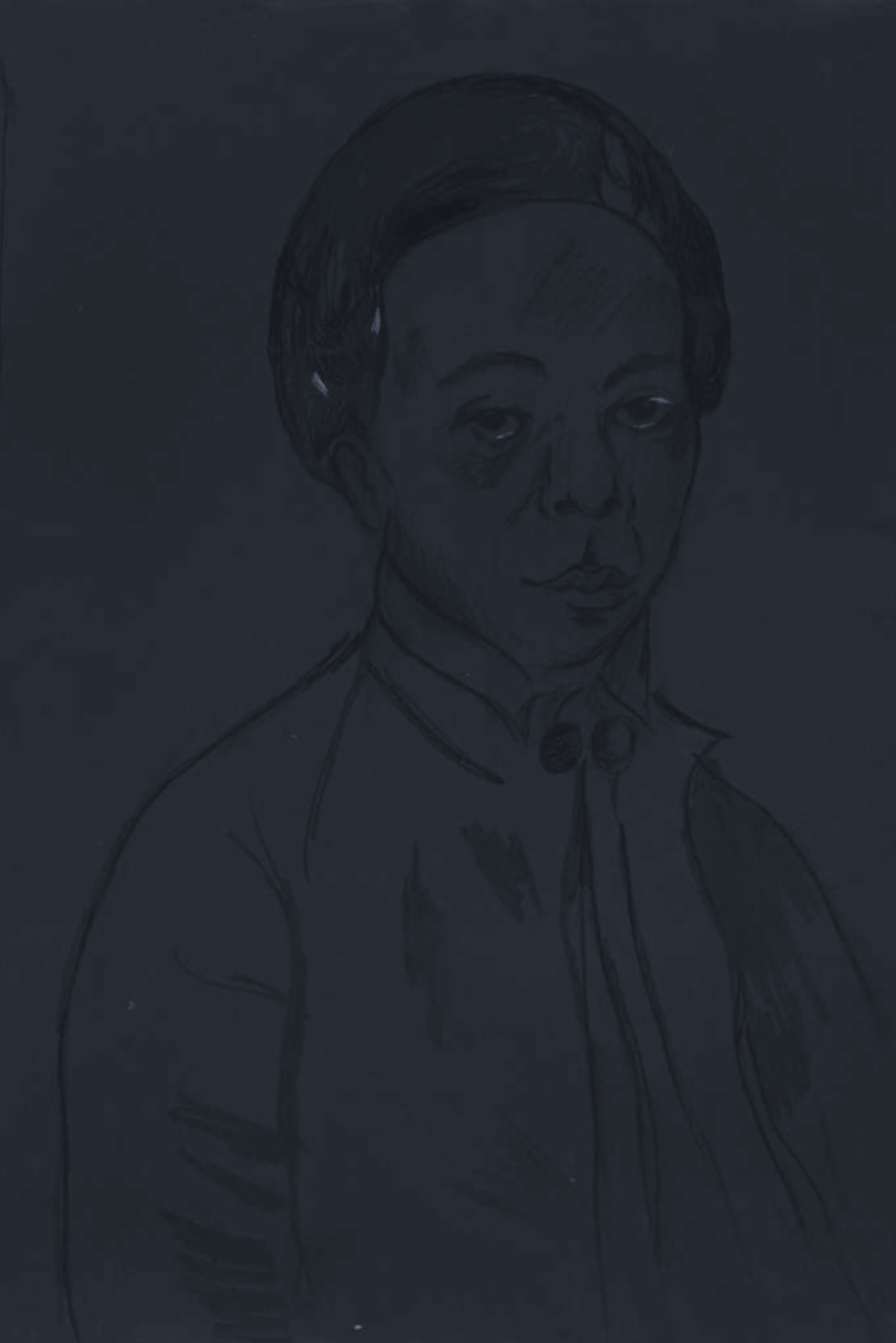

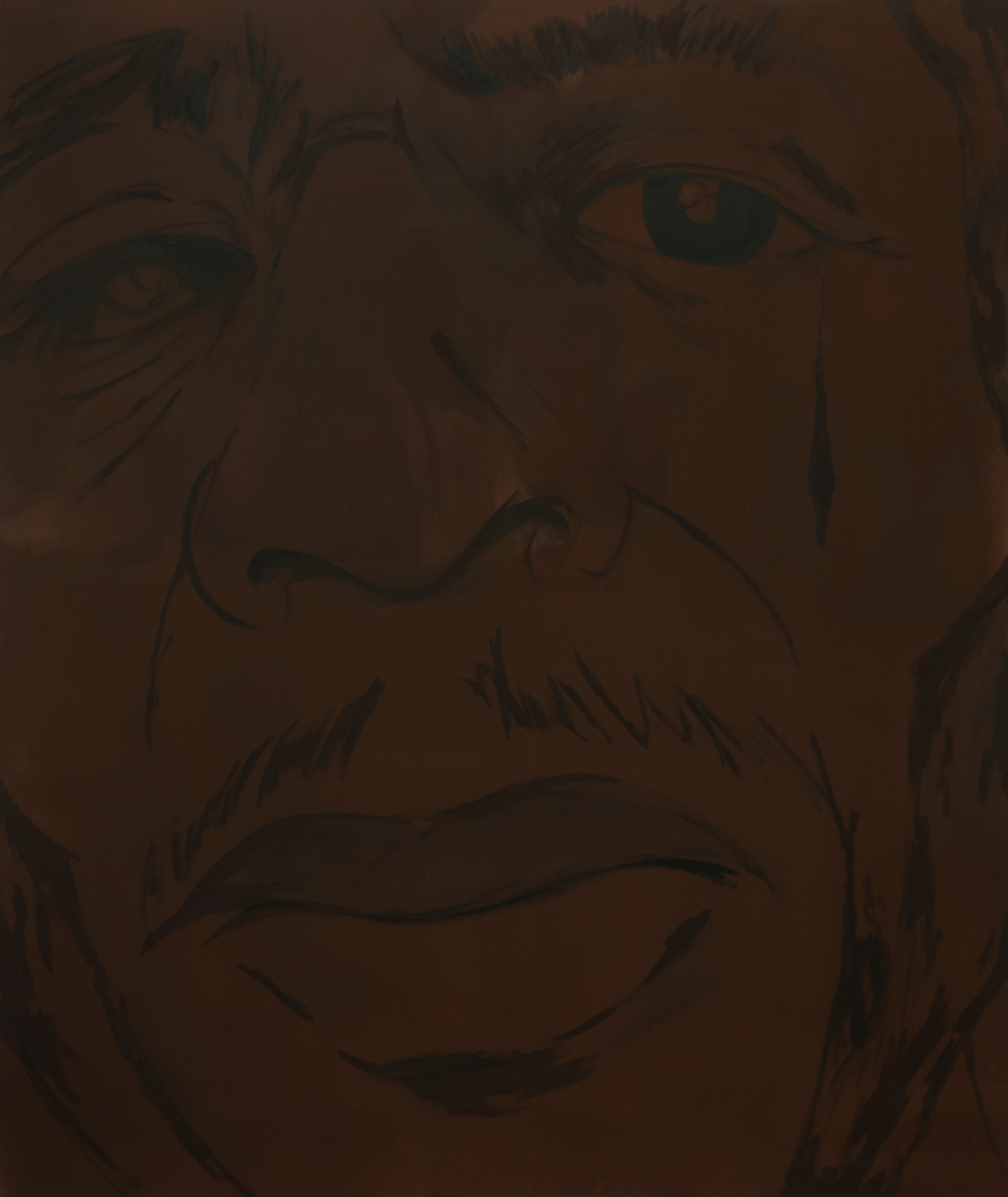

LM: Towards the end of my graduate program, I began wondering what happens when a person’s likeness becomes imperceptible, or begins to dissolve. Around the same time, I was asked whether I had considered making a self-portrait, and how I felt about representing myself in that way. That really opened up a new line of thinking for me. I believe it’s called The loves I have known.

Figure 13: Louise Mandumbwa, The loves I have ever known [detail], 2024, paper, canvas, graphite, ink and charcoal, 60 x 46.5 inches (152.4 x 118.11 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

Figure 14: Louise Mandumbwa, The loves I have known, 2024, paper, canvas, graphite, ink and charcoal, 60 x 46.5 inches (152.4 x 118.11 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

I have been writing about embodied memories and the idea that what you need to know about me may not be my likeness at all, but the things I love. I think about the sweetness of sugarcane and the memory of my hands at work and wanted to create a self-portrait that leaned into that, where the clearest element is not my face but the sugarcane I have written about so often. I am also working on an artist’s book that gathers these texts and fragments of writing. Many of my works share titles with the poems or essays that accompany them, to offer another entry point into the visual pieces. In this particular work, the figure is me, but I am almost invisible. What remains visible is the sugarcane, the foundational memory from my grandmother’s yard. By seeing that, rather than my face, you might understand something more essential about who I am.

The post-it you see there says, “What is possible in the illegible image? What exists in the gaps of the archive? In the failed transcription?”

LX: I didn’t initially realize the figure was actually you [laughs]. Why did you choose a three-quarter view that turns the gaze away from the viewer?

LM: I feel comfortable looking directly at the viewer, but early in my practice I made several front-facing portraits and later found the experience of seeing them together in a gallery unsettling. I felt like being stared at from every direction. That moment made me reconsider the gaze in my work. I began to think more intentionally about how awareness and intimacy operate between the subject and the viewer. The three-quarter and profile poses allow for a sense of interiority, and a space that feels more reflective than direct. I still love the intimacy of a frontal gaze but I now prefer when that closeness emerges through the viewer’s act of searching rather than through immediate eye contact.

What is possible in the illegible image? What exists in the gaps of the archive? In the failed transcription?

LX: I like that your face isn’t immediately visible in the piece. At first, I viewed the figure as almost statuesque. How did you achieve that beautiful blurred effect?

LM: I have been interested in collapsing mediums and letting printmaking, drawing, and painting overlap. The base of the work is a print made with materials that blur those boundaries, like liquid graphite, liquid charcoal, and silkscreen mediums. These combinations allow me to paint and print with what would usually be used to draw. In this piece, I layered paper over the canvas surface, pressed fragments of poetry onto it, and then rubbed them away by hand. The gesture created both erasure and felt revelatory like a record of my touch. I kept thinking about how we come to know the world. As children, we learn through our senses, through the feeling of things, and later language begins to narrow that way of knowing. Working with my hands allows me to return to that tactile understanding and let meaning show through touch rather than through language alone.

LX: As you describe the work, I can almost sense the sound and movement of the leaves, as if you had combed your hand through it. Do you have a robust archive at home of family photos to draw upon?

LM: I think my interest in archives comes from the lack of an abundance of documentation of my family’s history of migration. My parents moved from Zambia to Botswana, and my grandparents moved from the Congo and Angola to Zambia. With every migration, pieces of our story were lost. Even within one town, my family moved several times, and with each successive shift gaps widened or were created anew. There were very few family photographs, and each time I asked about one, I was met with a best guess of which relative might have it. Over time, I realized I was trying to build an archive for myself, to fill in what was missing. Language has also shaped this distance.

I only speak English, and my last living grandparent does not. Our conversations always require a third person, which reminds me of how much is untranslatable. Some meanings can never be fully carried over, no matter how carefully they are explained. That awareness deepened my interest in tactility. I know my grandmother less through her words than through the texture of her world, like the taste of her cooking, the things her hands made, the garden she nurtured…she once knitted and crocheted constantly, so her tenderness communicated entirely through touch. During the pandemic, when she was unwell and I was far away, I began to think about what I could still hold of her. I realized that my work grows from that same impulse of wanting to honor what remains when language fails, and trace love and memory through what is felt rather than spoken.

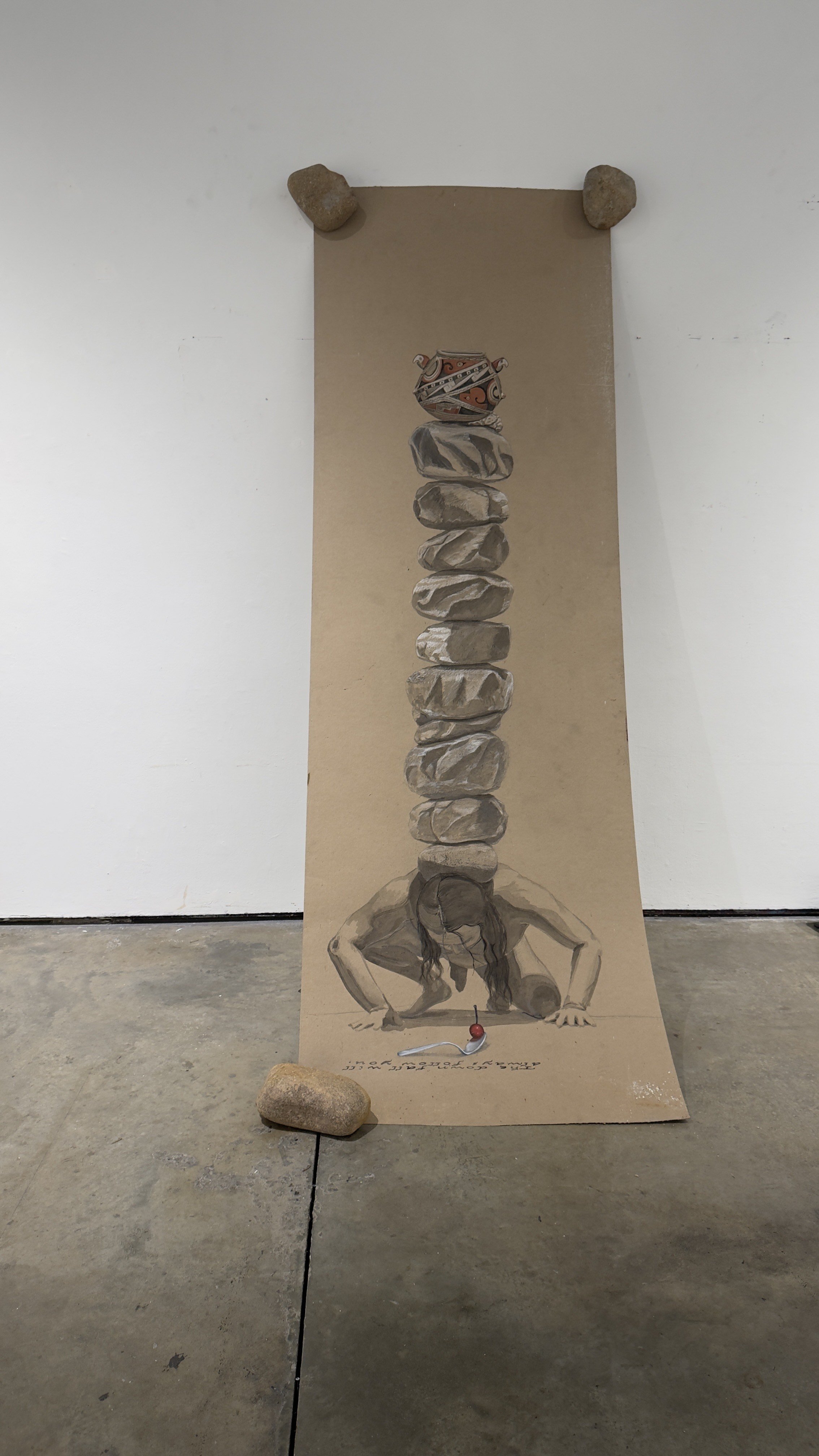

LX: Is Tell Me Something True a depiction of you with your grandma?

Figure 14: Louise Mandumbwa, Tell me something true, 2024, acrylic and oil on canvas, gouache and oil on paper, 20 x 16 inches (36 x 48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

LM: This painting is of my younger sister with two of my great aunts. It was taken during the trip when we visited my father’s home village. That visit felt like finding pieces of an answer I had been searching for. My father left the village when he was about ten and did not return until he was in his forties. When we visited together in 2023, he shared stories I had grown up hearing, but my great aunts, Margaret and Nama, remembered them differently. Their recollections recontextualized everything. I realized that my understanding of this place had been built on secondhand memories recounted decades later. That trip also revealed something about my own name.

The botanical piece beside the photograph refers to my maiden name, Mandumbwa, which I learned comes from the Ndumbwa tree, native to that region. The word itself, Mandumbwa, refers to the fruit of that tree. My family settled near the groove where those trees grew, and the name became tied to the land. For me, that discovery elucidates how a name can serve as a kind of map for locating both family histories and belonging within a landscape.

LX: That’s so interesting. I love how deeply you engage with theory and the natural world. It’s rare to see. The botanical research in your work is such a beautiful entry point, especially in relation to trade and movement. I’m also curious about your work End Notes.

Figure 15: Louise Mandumbwa, End notes, 2024, concrete, wheat paste and newsprint, 14 x 66 x 3 inches (35.56 x 167.64 x 7.62 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

LM: End Notes is a cast concrete work that grew from my interest in how information circulates across different places. In the United States, zine culture carries a sense of accessibility and exchange. In southern Africa, that same impulse often takes shape through printed pages wheat-pasted on concrete walls outside homes and shops, where they weather, layer, and form an informal public archive. I wanted to create an artist book that felt rooted in that context. I learned letterpress printing, traditional bookbinding techniques and looked at self publishing methods, but concrete felt closer to the material reality of how ideas move where I am from. I cast a heavy slab, applied fragments of my poetry to its surface, and then weathered the paper away. What remains are only traces like page numbers, faint marks, and remnants of language. The piece slows the act of reading and asks what knowledge might live in what has been erased.

LX: How heavy is it, and how did you manage to hang that piece?

LM: With difficulty [laughs]. The piece is about four-and-a-half inches deep, with an empty cavity in the back and an inset forty-five-degree French cleat inside. I wanted the piece installed slightly lower than the rest of the paintings, since it is called End Notes and was meant to feel a little offset. During installation, we discovered the wall was uneven and it turned out to be a false wall. We finally had to move it to another spot at midnight. By the end, I just said, “If it’s on the wall, I’m happy.” That exhausting experience added to the work honestly [laughter].

LX: As an “end note” question, if you could imagine your ideal solo show, what would it look like, or where would it be?

LM: I’ve imagined an exhibition built around iteration and memory. There’s a work I made called All Artist Proofs that features many small faces, some of which are clear, some of which are blurred, and some are almost gone. I love the idea of showing two related works in different rooms, where each holds part of the image. You would have to carry the memory of one as you walk to the next, piecing them together in your mind. My dream show would ask the viewer not just to look, but to remember and to connect the fragments kind of like breadcrumbs. I imagine one room as a living garden filled with sugarcane, yucca, and plants from different places I’ve called home, like a hybrid garden of memory and geography. There’d be an artist book with page numbers or fragments that guide you toward other parts of the exhibition.

Photo: Arielle Gray

Louise Mandumbwa

Louise Mandumbwa (born 1996, Francistown, Botswana) is an artist working in painting, printmaking and drawing to explore ideations of home, figurative and botanical works. Her practice is a counter mapping endeavor examining the ranging registers or memory through material exploration, the illegible image and failed translation. An immigrant artist her works revisits sites of both familial and diasporic history to and appends them with affect and the anecdotal. Mandumbwa holds an MFA in Painting and Printmaking from Yale university as well as a BFA in Painting from the University of Central Arkansas. Her work has been included in recent group exhibitions at Sakhile&Me (Frankfurt, DE, 2025), Chili Art Projects (London, UK 2024), Spurs Gallery (Beijing, CN), David Castillo (Miami, FL), The Wright Museum (Detroit, MI) and Yossi Milo (New York, NY). She was a 2024 recipient of agrant from the Elizabeth Greenshield foundation and the Elizabeth Canfield Hicks award from Yale University. She has completed residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2024), The Sam and Adele Golden Foundation for the Arts (New Berlin, NY 2022) and Visual Arts at Chautauqua Institution (Chautauqua, NY 2019) and Louise lives and works in New Haven, CT.

Instagram: @louise_mandumbwa

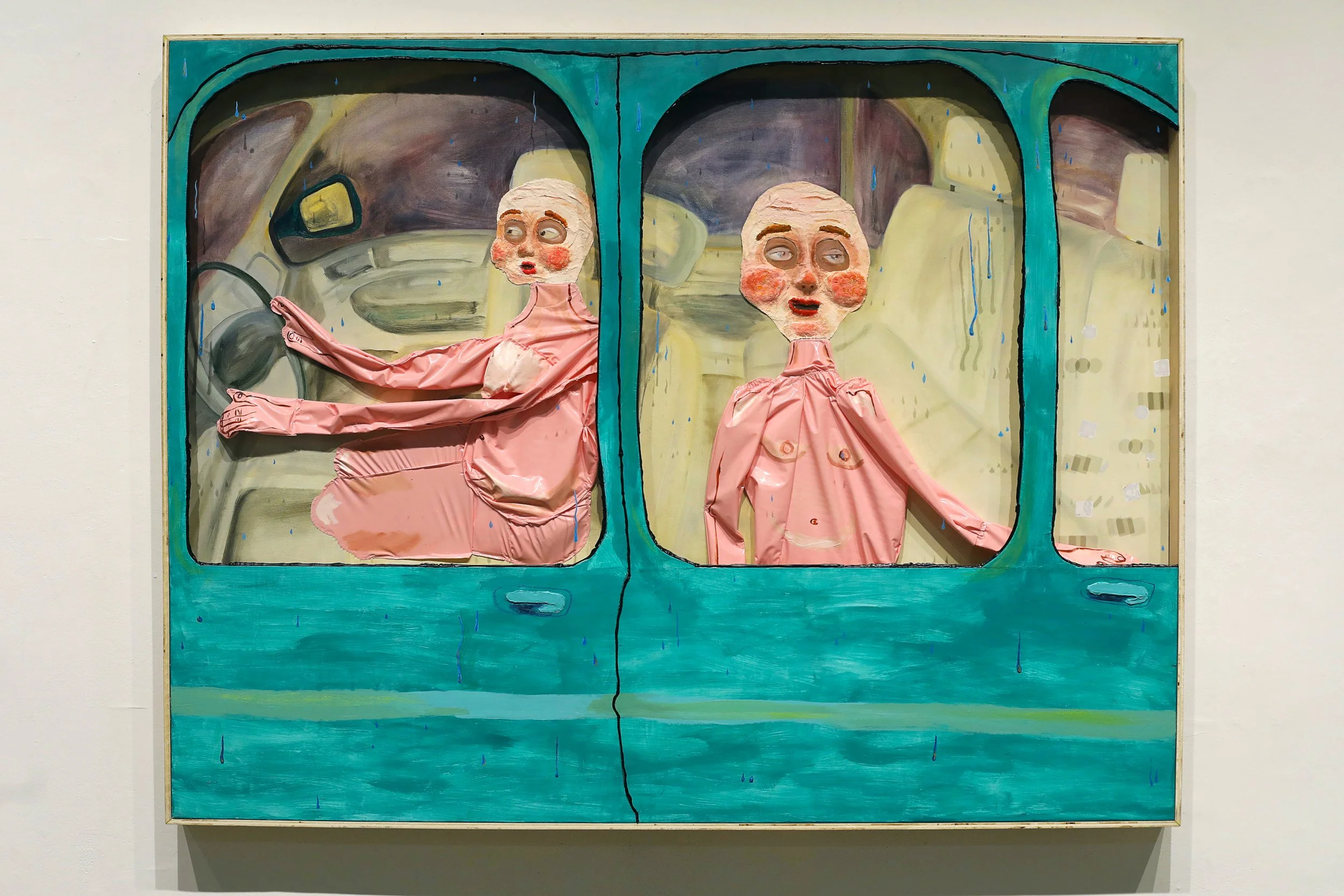

The In-Between Moments: In Conversation with Nadia Younes

Throughout her multimedia practice, Nadia Younes offers glimpses into construction sites and liminal spaces to investigate themes of displacement and instability. Younes speaks with Lara Xenia about her family history, love for junkyards, and her material explorations.

Figure 1: Nadia Younes, Distilled Emptiness, 2024, oil on panel, 48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Lara Xenia: What’s a core memory of a place from your childhood?

Nadia Younes: One of my strongest memories is from the coast of Mauritania. My parents had a tough time there, and I was so young that I only remember bits and pieces. The clearest memory I have is of the dirt roads covered in seashells. I once picked one up, and a cascade of tiny shells spilled out. For a while, I actually thought that's how babies were born [laughter].

LX: That’s so sweet. I didn’t realize you spent time in Mauritania when you were little.

NY: Yes, I moved around a lot as a child. I was born in Nazareth, but when I was three, we moved to Mali, then to Mauritania and Jordan. Once we returned to Israel when I was five-and-a-half, I started learning Hebrew. Let me give you some family history…

Figure 2: Nadia Younes, Nature of Matter, 2022, oil on panel, 8 x 6 feet (243.84 x 182.88 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

In 1947, my grandma was born in Ashkelon (historically known as al-Majdal/Asqalan) in what is now Israel. A year later, the 1948 Arab–Israeli War (al-Nakba/War of Independence) broke out, and her family was deported to Sinai, so she moved to Cairo. My dad was born there as the youngest of six children. Unfortunately, my grandfather died young, so my grandma had to move with her six children to Gaza, where she was at the mercy of her family. On the ground floor of the house she lived in, she ran a small convenience store selling cigarettes, juices, and snacks, on a route used mainly by the Israeli army from a nearby base and by settlers from Gush Katif.

I’ve been to the West Bank, Palestinian territories, and Jordan, but never to Gaza, because after I was born it was after the two intifadas, and the border was closed…you needed very special permits to get in or out.

Figure 3: Nadia Younes, Past Observation Process, 2022, 8 × 6 inches (20.32 × 15.24 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Figure 4: Nadia Younes, What’s Missing, 2023, oil and inkjet on paper, 35 x 34 inches (88.9 x 86.36 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

LX: Oh wow, so your family was based in Gaza?

NY: Yes, my grandmother and her six children were still living there. In the mid-1980s, a U.S.-based real estate group approached her several times to buy the house and shop, saying the location was strategic for the military and nearby settlements. They even offered her Israeli citizenship. She initially rejected the offer, but then she acquiesced when the Gaza authorities pressured her to close the shop since many of her customers were Israelis. As a young widow raising six kids on her own in a tough environment, she eventually had no choice but to leave. When my dad was about sixteen, they packed up quietly one night and left and he ended up moving to Nazareth.

In the late 1990s, my mother, Tatiana, came to Israel as a tourist from Kronstadt, which is a small naval island near St. Petersburg. She had a hard time in Russia after the Soviet Union fell. My parents met at a nightclub in Nazareth. Her father struggled with alcoholism, and her mother, Liudmila, was very supportive, but they had lived through times of boiling their own shoes for broth.

LX: That’s really crazy. Would you say displacement and family traumas actively inform your creative process, or do you notice these influences more in retrospect?

Figure 5: Nadia Younes, Emptiness as a Verb No. 3, 2025, oil on panel, 12 x 9 inches (30.48 x 22.86 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: That's a great question. When I was younger, I turned to painting and crafts as a safe haven from my turbulent childhood, and mainly made self-portraits. I later shifted to depicting construction sites and industrial spaces, which I see as systems of neglect that raise questions about physical bodies, access, and restrictions. Moving from country to country without any stability made these spaces feel permanent to me because no matter where I went, there was always construction and broken architecture.

Over time, I realized that most of life unfolds in the in-between moments, rather than in cathartic ones. I’d notice an air duct on the street and see it as an entity in itself or a truism. I try to employ trompe l’oeil effects and realism to destabilize viewers’ assumptions by connecting to sites that feel like “no man’s land,” where the ground seems pulled from under me. I like the agency that materials possess, like when materials start looking back at you or the object becomes the subject.

LX: Your approach to architecture is fascinating. What informed Nostalgia for the Nonexistent and Nostalgia for the Missing?

Over time, I realized that most of life unfolds in the in-between moments, rather than in cathartic ones.

Figure 6: Nadia Younes, Nostalgia for the Nonexistent, 2024, oil on panel, 36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 69.96 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Figure 7: Nadia Younes, Nostalgia for the Missing, 2024, oil on panel, 36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.94 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: As someone who lived in Israel for a while, I immediately recognized the architectural codes of the region when Sergey Kadochnikov, my best friend and collaborator from Jerusalem, shared the image with me. It was quite poetic to paint a site I never physically occupied, and to test how memory, fantasy, and distance could produce its own language. I honestly felt compelled to paint his photographs after moving away from our shared life and creative partnership.

LX: That’s so fruitful to have a friendship like that. So your air ducts embody bodies?

Figure 8: Nadia Younes, Nowhere, 2024, oil on panel, 8 x 6 inches (15.24 x 20.32 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: Yes, or something that’s unfamiliar. When I deal with construction sites and industrial areas, usually I see them as a universal code for temporality, access, social hierarchies, and gender roles, since construction sites are usually dominated by men or by me and my studio apprentice.

I love going to the metal junkyard in New Haven [smiles]. Sometimes I honestly prefer to go there rather than the museum to get more inspiration. I just feel alive there [laughter]! I’m intrigued by the transactional dynamics of how as two women my apprentice and I have to adjust to being allowed in those spaces to get what we need from the junkyard.

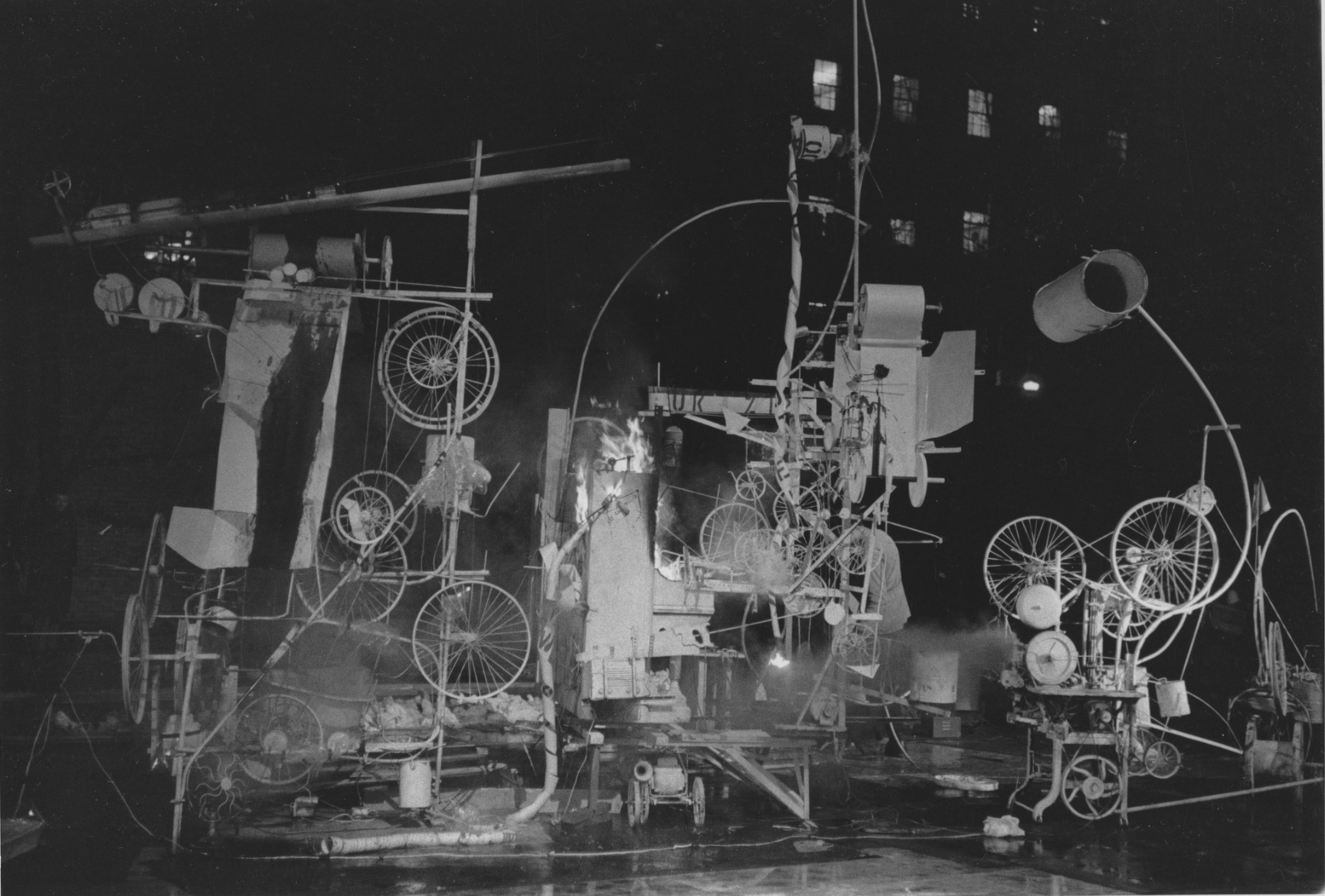

Figure 9: Jean Tinguely, Installation view of the exhibition Homage to New York: A self-constructing and self-destroying work of art conceived and built by Jean Tinguely, March 17, 1960. Photographic archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, New York (IN661.1). Video footage: courtesy © Museum Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6dgGu2w3Qvo

LX: I like that you like literal detritus. That kind of reminds me of how Jean Tinguely salvaged bicycles and scraps from Newark’s junkyard to create Homage to New York. He showcased his “suicidal sculpture” in MoMA’s garden in March 1960 and the fire department had to put it out after it burst into flames.

NY: I could totally see myself doing that [laughter].

LX: What’s the story behind the work with scrawled writing on the walls?

Figure 10: Nadia Younes, Ouroboros (Novembers), 2024, oil, charcoal and paper on panel, 72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: I made this painting in November 2023 when I was grieving my dog’s passing, my mom’s relapse into alcoholism, and the outbreak of war, so I chose to expose the panel and mark it with charcoal and pencil as I wrestled with my thoughts. I was dealing with an eating disorder and a sudden loss of control. Even small differences, like food labels switching from grams to “per serving” felt disorienting.

I’d often stare out the window at a nail in the frame and the empty blue sky beyond to ground myself, and in that same corner, I had taped a church pamphlet I once picked up that said, “Why must I suffer?” I wrote it largescale across the gallery wall in large charcoal next to complement this work. I often return to the image of the ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail, bringing itself to life and killing itself in a never-ending cycle.

LX: Oh, I’m sorry you went through that. It's interesting that you chose ouroboros as a reference too. Were those dark times prompted more by your external environment that shaped it?

NY: It was absolutely circumstantial because in my heart, I believe that there is a lot of love in the world, and a lot of beautiful reciprocity. We can choose to surround ourselves with kindness and compassion daily. Looking at it now, a lot of my work deals with pain…I don't think that I paint happy subjects…[laughs]

LX: Do your thesis sculptures grapple with that? Take me through your process.

Figure 11: Nadia Younes, Another Fine Portal Mess, 2025, mixed media, 45 x 45 inches (114.3 x 114.3 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Figure 12: Nadia Younes, Another Fine Portal Mess (detail), 2025, mixed media, 45 x 45 inches (114.3 x 114.3 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: I see those two works in tandem with one another. For those works, I wondered what it meant to carry something with you when you’re uprooted, so that inspired both works.

Another Fine Portal Mess was a failed attempt to cast Compression Field. For Another Fine Portal Mess, I first used a trash bag coated with tar as a mold and tried using five gallons (so 102.5 pounds) of resin to make it. When I used a heat gun to get a globby effect, it grew too heavy, sank, and leaked, revealing the black layer underneath. The fumes were so strong the safety office cleared out my studio and banned me for three days because it was super toxic. I’m not proud of it, but it shows how volatile my process can be. Back in Israel, I worked with melting lead and plastic tarps. They respond to touch and pressure in a way metals like aluminium or steel can’t because it has a low temperature, and when it melts, it's shiny.

LX: Lead? Like Caravaggio lead? Nadia, that’s insane! [Laughter] Also, how heavy is this thing?

NY: About 50–60 pounds. Two people need to lift it. Yale’s department nearly barred me from showing it in the thesis show because of toxicity concerns, but by the thesis show Another Portal Mess had already stopped off-gassing, and Compression Field was produced safely, even as it kept resisting and leaking onto the floor of the gallery. For me, though, the instability and volatility of these works is essential. I’m drawn to objects that behave as if they have a life and desire of their own.

Compression Field a successful attempt. I wanted the bag to conjure a body, a womb, or a vessel that couldn’t hold its contents within. I cast it using resin in a large industrial chemical bin using sand and water. The water acted as a placeholder for the resin, and displaced it into a kiddie pool as I poured. I lined a trash can with a trash bag as a makeshift mold and worked around sand reserved for pewter. When I pulled it from the mold, it seemed to have shaped itself [laughs].

I wanted the bag to conjure a body, a womb, or a vessel that couldn’t hold its contents within.

Resin doesn’t react well to moisture, so the environment was hostile from the start. I think constantly about temperature and conditions, and about how to make metal and other stubborn materials feel warm, responsive, and almost living materials. The result felt less like control and more like a negotiation with the material. I then filled the interior with flexible metal conduits salvaged outside the Jewish Life Center’s construction site at Yale. It still had fragments of the wall and its residue felt poetic, like a system trying and failing to contain its past or history.

LX: That’s really cool. The way you connect belonging, volatility, and transience to self-understanding is moving. What was that vision?

NY: Compression Field emerged from a visceral childhood memory of carrying glass bottles of Heineken for my mother in a black bodega bag while my dad was at work. When I tried to ration her beer, she lost control, so I called the police, expecting protection, but they only questioned who sold the alcohol to a child. In the end, the blame fell on me.

Figure 13: Nadia Younes, Compression Field, 2025, resin, FMC, wall chunks, rusty chain, 30 x 20 x 20 inches (76.2 x 50.8 x 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes. For additional documentation please visit: https://nadia-younes.com/work/mfa-thesis-yale-school-of-art

That moment revealed how fragile support systems can be and characterized functional and dysfunctional systems. As a kid you believe you have choice, but that illusion leaves you carrying a responsibility for things beyond your control. So both works are a response to that rupture.

LX: It seems like you like that dichotomy.

NY: I really do seek it. I enjoy being in that tension.

LX: Which artists have inspired you?

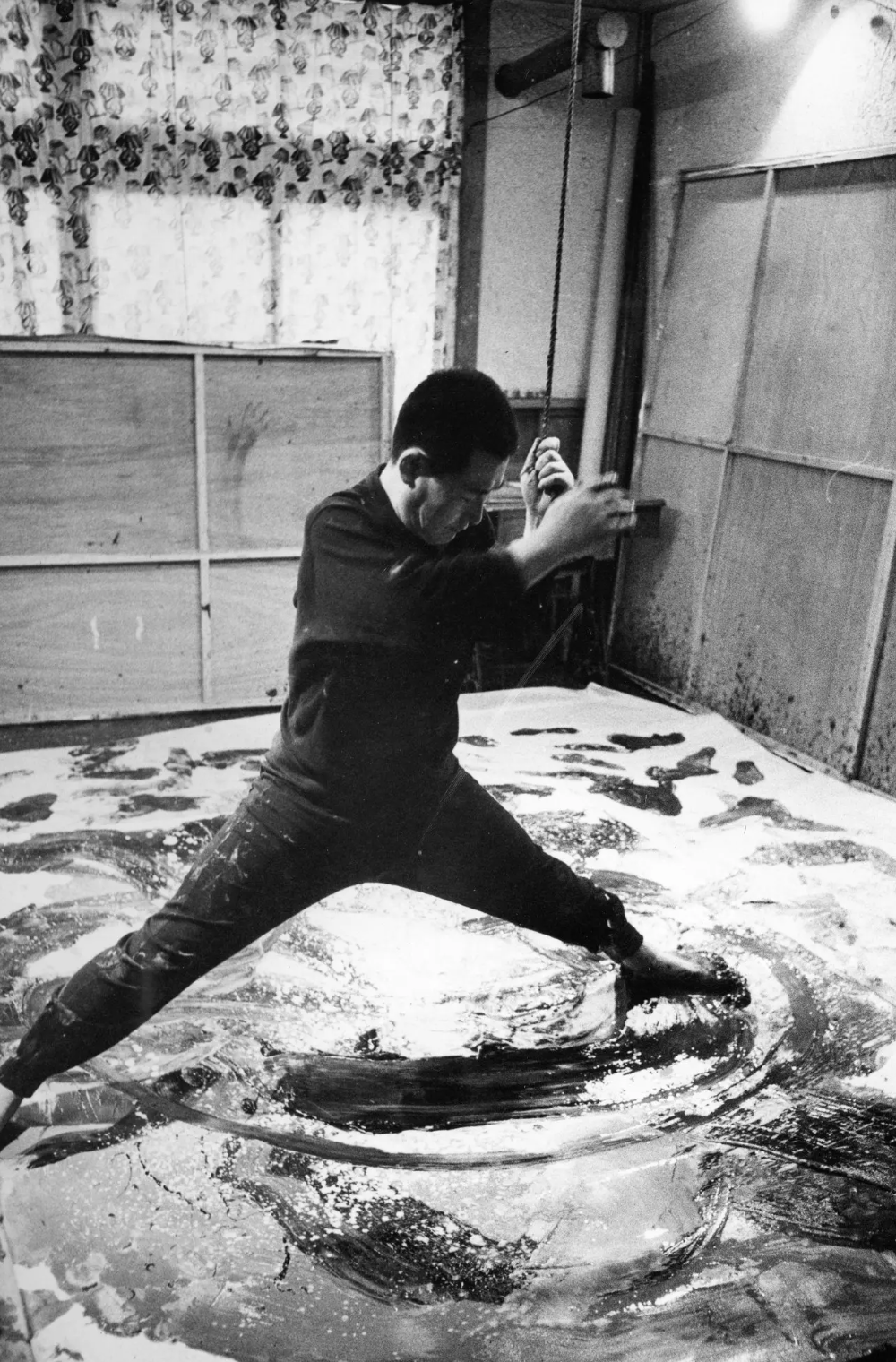

Figure 14: Kazuo Shiraga in his studio, 1960. Photo: courtesy Amagasaki Cultural Center and The New York Times. Image source: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/02/arts/international/art-world-rediscovers-kazuo-shiraga.html

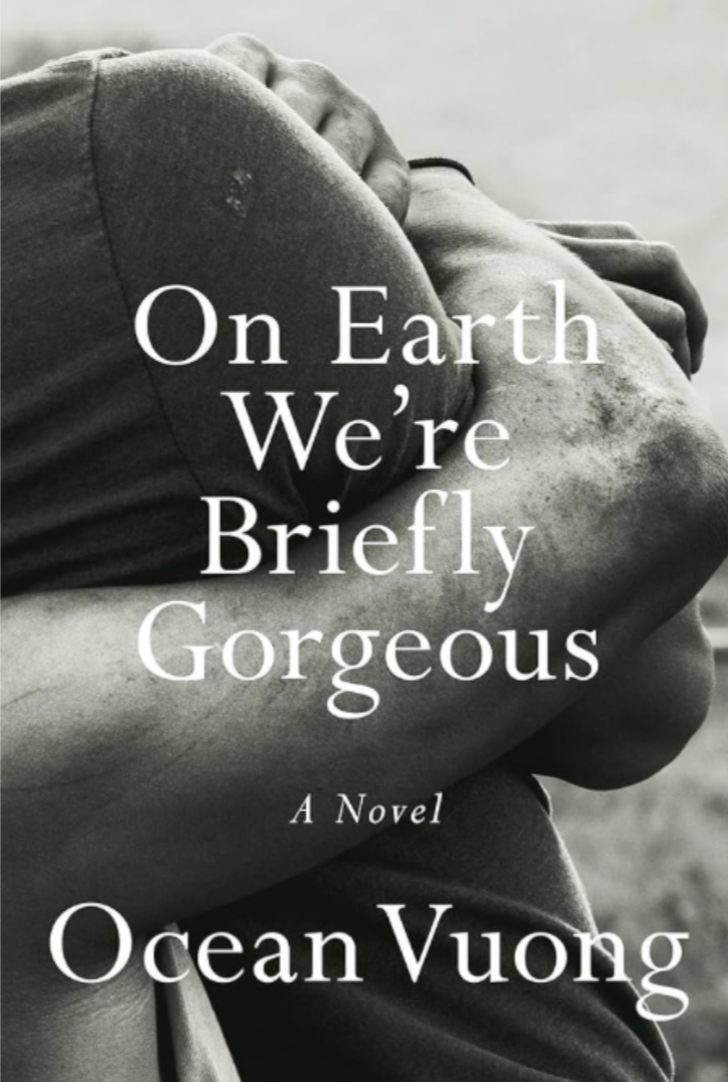

NY: I think a lot about Kazuo Shiraga, the Japanese Gutai artist. I first saw his work at MoMA in 2021, soon after coming to New York. I love the tension between the delicacy of the papers and the weight of the paint and the raw evidence of the body in his work. I also think about Sylvia Plath in relation to that a lot and really resonated with The Bell Jar for its portrayal of depression and the way she framed an autobiographical story as a novel.

LX: Oh, I love the Gutai group and that’s on my book list. Is there anything you want to be known by?

That moment revealed how fragile support systems can be and characterized functional and dysfunctional systems.

NY: As an artist of my time, yes. I want to open the possibility that a lot of truths can exist simultaneously, and that in terms of our existence, we exist and therefore we suffer. I think about it as universal. I want to relate to the viewers and to people on an emotional level.

LX: What’s something that you live by?

Figure 15: Nadia Younes, Phantom Fragments, 2022, oil and charcoal on panel, 8 x 11 feet (243.84 x 335.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: J. Cole is one of my favorite artists, and he has a line I love: “Sometimes you gotta step away, do some living, let time provide a new prescription.” I feel that deeply because I feel like everything in life has a price.

Nadia Younes

Nadia Younes is an interdisciplinary artist working across painting, sculpture, installation, video, and writing. Born in Nazareth to a Palestinian refugee father and a Soviet immigrant mother, she moved between Israel, Mali, Mauritania, Jordan, and Russia. This transitory upbringing shaped her sensitivity to displacement, instability, and overlooked spatial systems, concerns that are central to her practice.

Her work explores tensions between surface and structure, access and refusal, containment and collapse. Drawing from industrial materials and urban demolition sites, she merges classical painting methods with cast resin, paint skins, flexible metal conduit, and other construction remnants. She treats these materials as bearing the memory of bodies in flux, reflecting systems of labor, gender, and survival. Multilingual in English, Arabic, Hebrew, and Russian, Younes approaches materials as she does language: as codes that can be bent, fractured, and reassembled.

Recent presentations include PowerLine at Perrotin, New York (2025), a public video screening with ZAZ10TS in Times Square (2024), and the solo exhibition Elusive Territories at The Study at Yale (2024). Select works include Interference Pattern, a mirrored environment featuring a suspended car and circulating liquids; Site of Failure, a kinetic installation composed of acrylic paint skins; Compression Field, a 450-pound resin sculpture embedded with demolition debris; and Second Lesson in Boundaries, a trompe-l’œil oil painting that reflects surveillance and fencing systems in Israel and the West Bank.

She holds an MFA in Painting and Printmaking from the Yale School of Art and a BFA from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. Her training includes scientific glassblowing, lithography, marble carving, and classical studies at the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburg. Younes has served as a graduate assistant at the Yale School of Art, taught at Bezalel, and engaged in community-based initiatives. She received support from residencies such as the Vermont Studio Center and ISPMFA, and was the recipient of the Winsor & Newton Award for Excellence in Painting. She is currently based between New Haven and New York.

Nightvision: In Conversation with Z.T. Nguyễn

Z.T. Nguyễn speaks with Lara Xenia about how insects, queer theory, and revolutions inform his rigorous drawing practice.

Figure 1: Z.T. Nguyễn, A sort of delicious terror (detail), graphite, colored pencil, and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 83 x 73 inches (unframed) (210 x 185.42 cm [unframed]). Photo: courtesy the artist, Perrotin Gallery, and Guillaume Ziccarelli © Z.T. Nguyễn and Perrotin

Lara Xenia: What is “home” for you?

Z.T. Nguyễn: I'm actually in a temporary living situation right now, with my parents. I do feel comfortable here since I'm around my family members, but knowing it won't last makes me feel more like a visitor, like I'm untethered and floating…not just in terms of where I'm living, but also my community, my belongings, not having a studio while I'm here. So maybe “home" for me is something that’s steady under my feet. It doesn't necessarily need to be a place, but something that’s reliable and rooted.

LX: I'm really interested in how you configure forms in space and cropped bodies within your compositions. What got you interested in figurative works?

ZTN: Representing the body—mostly my own body—has always been a pretty natural inclination for me in my work. I'm very aware of my body language and physical sensations in public spaces because they’re indicative of my social surroundings. How am I being perceived and how am I perceiving other people right now? The answers manifest in my stomach, on my skin, in the way I speak and make eye contact. I think this bodily social awareness is heightened by the fact that I'm queer and not white. That's definitely something I instinctively pay a lot of attention to, having grown up in a rural community that had very few other people like me.

Figure 2: Z.T. Nguyễn, Waiting, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 42.25 x 32.25 inches (107.32 x 81.92 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

So the cropped or fractured body is sort of my way of zeroing in on the physical sensations that emerge from otherness. I think there's something about incompleteness that I'm interested in, too. Like, the incompleteness of identity, of history, or even the incompleteness of my grasp on the Vietnamese language, which is what I speak with my family in a really fragmented manner.

LX: I love that. Are you first gen American as well?

ZTN: I’m part of the first generation in my family to be born here, yes. But my parents came here when they were kids, so they’re quite American…I don't have a lot of the same burdens that other young Asian Americans have, like needing to translate conversations and documents for my relatives. Still though, my family's histories as refugees and their experiences with displacement and marginalization in places like Oklahoma, Florida, and Maryland are deeply important to me.

LX: I see. And what about insects? How did your moth drawings first come about?

ZTN: The moth motifs are part of a more general interest I've had for a while in nocturnality and the nighttime, but they’re actually a way for me to think about my family, too. Most of the moths I draw are based on a group known as “Asian American moon moths,” which includes the Luna Moth and is part of a larger moth family called Saturniids. I was originally drawn to them because of their classification as “Asian American,” which is used by entomologists to describe their geographic range from Afghanistan and the Indian Subcontinent eastward, all the way to the Americas. But a key feature of these moths—the thing that led me to draw them so much in my work—is that they lose functionality of their digestive systems after they pupate. Rather than eating and nourishing themselves, their sole purpose in their final, most beautiful stage of life is to mate and provide for the next generation. And after just a few days as fully-formed moths, they die.

Figure 3: Z.T. Nguyễn, Moth, graphite and wall paint on letter-sized sheets of paper, 16.25 x 8 inches (41.28 x 20.32 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

LX: In what part did that feel like your family?

ZTN: The sacrifice in having no other option but to provide for the next generation. Luckily my family members are indeed able to eat, and have fully-functioning digestive systems, for now [laughs]. But I think that the biology of these moths feels analogous to my parents’ and grandparents’ values and how I interpret their struggles in the US. Moths are primarily active in the night, which is a larger theme in my practice, as I mentioned. The night, for me, has a lot to do with waiting and transformation and the potential energy that builds before change occurs. In my piece Moth, which I did in the fall of 2023, I cut a drawing of the night sky into the silhouette of a moth. There's something about the briefness of an Asian American moon moth’s lifespan versus the ancientness of stars that appeals to me. What does it mean to compress these giant, almost incomprehensible cosmic objects in the night sky—most of which are larger and sometimes older than our own solar system's sun—down into the shape of something as simple and short-lived as a moth? I think it speaks to the infinitude I see in my family members and even in myself.

LX: And what about the mosquitoes that often show up in your work? Are those related to your family, too?

The night, for me, has a lot to do with waiting and transformation and the potential energy that builds before change occurs.

ZTN: To a degree, yes. Mosquitoes are also nocturnal like moths, which is a big reason why I tend to draw them. But unlike moths, especially large and beautiful Asian American moon moths like the Luna Moth, mosquitoes are basically universally despised [laughs]. The first drawing I made at Yale in 2023 was called Dandelion, and it had these mosquitoes in it that were menacingly large and chunky, flying around two pairs of feet and a dandelion that had lost all its seeds and petals. I was thinking about the floor and how it's often overlooked or considered dirty, but how it's also the plane that supports our bodies. I was also thinking a lot about weeds and overgrowth. Even though there's a lot of beauty to be found in that space, the mosquitoes were there as a sort of threat. I’m really interested in the precarity of mosquitoes, and how they might disrupt the otherwise tranquil register of an image. That precarity certainly resonates with me when I think about my family's history, and mosquitoes themselves also have a direct reference to heat and the tropics.

Figure 4: Z.T. Nguyễn, Dandelion, graphite and wall paint on letter-sized sheets of paper, 68.75 x 26 inches (174.63 x 66.04 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

My mom is from Laos and my dad is from Vietnam, so I also think a lot about the tropics as an alternate modality. The ways that heat, humidity, infertile soil, and challenging topographies force people to abandon ways of living that are standard in temperate regions, which often include countries in the Global North. That environmentally-forced turn away from colonial norms is really inspiring to me. Like land itself rejects colonization. There's a lot we can learn from it. That being said, I've never lived in either Laos or Vietnam myself, but motifs like mosquitoes, which are often associated with heat and the tropics, are reminders that I'm still deeply invested in where my family is from.

LX: I can see how they evoke heat.

ZTN: Yeah. Here in North America, mosquitoes are only really out on summer nights, which kinda feels really queer to me. Or more specifically, gay [laughs]. I was taking this class called Queer Strategies at Yale, which is typically offered every fall in the School of Art; a few of us called it “gay class” as a joke [laughs]. And I talked about mosquitoes a lot during that class, actually. Beyond the “summer nights" thing, mosquitoes are also associated with disease, they suck on bodily fluids, they're mostly invisible until you spot them up close, they're widely regarded as pests, and many people actually want them vanquished from the face of the planet despite them being vital to ecosystems in basically every biome they occupy. Sounds pretty gay to me [laughs]! But in all seriousness, I don't want to use them as an anthropomorphic symbol or anything because mosquitoes are also responsible for more human deaths than any other animal… Again, I'd say it's more about the precarity that they evoke. There was a lot of queer theory we read in Queer Strategies that complemented this pretty well, too.

That precarity [of mosquitos] certainly resonates with me when I think about my family's history, and mosquitoes themselves also have a direct reference to heat and the tropics.

LX: I love queer theory. Did you read any Whitney Chadwick or Richard Meyer?

ZTN: Not for the class, but on my own, yeah! From the Queer Strategies reading list there was Ursula K. Le Guin's Author of the Acacia Seeds, Gregg Bordowitz's Questions, and Eva Hayward's Spiderwomen, which were all particularly impactful on me. Outside of that class, though, another faculty member brought to my attention this poem by John Donne called The Flea. In the poem, two lovers can only meet through a flea that bites both of them, so their blood could mingle inside of its body. She thought it was relevant to my mosquito drawings, especially Dandelion, and I agreed. I was really struck by it and have continued to think about it a lot—that gross but also sweet and tragic sentiment. It was really interesting to me. It felt in sync with the weird affective mode that I was wanting to work with, and it still resonates with me now.

LXM: Could you tell me about Mosquito Star?

Figure 5: Z.T. Nguyễn, Mosquito Star, graphite and wall paint on letter-sized sheets of paper, 32 x 31.5 inches (81.8 x 80.01 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

ZTN: Sure! I've already talked about mosquitoes, so I guess I can talk about the star as a separate motif. There are two types of stars I frequently return to in my work: the naturalistic star, which I used in Moth, and then the five-pointed star, which is a representation of the naturalistic star, but an oversimplification of it. It's like cutting down a real star—like, an ancient, celestial entity—into a simple, easily reproduced shape that's mostly found in human political contexts. I'm really interested in that oversimplification as it pertains to politics.

Mosquitoes fly around pretty randomly, without any sense of order or synchronization; so, for them to form up into a five-pointed star like the one in Mosquito Star would be, like, really unusual and unlikely. So, I’d say this work is really about the unnerving and precarious nature of human politics. This kind of star is also a big part of the Vietnamese flag, so I’ve also thought a lot about this work in relation to the circumstances of modern Vietnam's formation, which was an immensely violent part of history, largely because of French and Japanese colonialism but also more famously because of US intervention and escalation. So I think Mosquito Star, and my use of five-pointed stars in general, could be understood as a sort of a critique of the extreme measures that powerful countries took in order to assert control and influence in Vietnam during that time of revolution. This year, 2025, marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the US Wars in Southeast Asia, including the Vietnam War, which is still a point of extreme sensitivity for a lot of people.

LX: It’s really brave that you’re even approaching this in your art. Artists are always exploring themselves, sometimes subconsciously, through what they absorb day to day. As a child of immigrants, I think grappling with that history is especially powerful because you’re trying to tap into your family’s narrative.

ZTN: Thank you. Yeah, and the five-pointed star is not unique to Vietnam, either. These stars are on a lot of flags: the US, Morocco, Pakistan, China, Honduras, Somalia, Myanmar, Cuba. The list goes on and on and on. And so that oversimplification that the shape does to naturalistic stars—that emphasis on the unnatural, sharp-edged mechanics of human politics—it's a reminder that it's really something that’s happened globally, not just in Vietnamese political history. And what’s more is that history is still ongoing today, too. Like, in the US, Southeast Asian refugees are still being specifically targeted and deported by the masses, which has been quietly going on for almost two decades now, and no one seems to be aware of how deeply it’s been disrupting our communities. And it's only, like, one of many loose strings from the wars that were left untied. It just makes me think about how many political injustices are still very much ongoing and still unfolding today all over the world, whether or not they're considered “over,” you know?

LX: Do you think of that temporality at all within your work?

ZTN: Definitely. I'd even say temporality in general is another kind of subject matter or motif for me, just like bodies or insects or the night, since a lot of the paper surfaces I draw on are folded and can be carried in a pocket or a bag. I like the idea of a drawing being carried by me—or by anyone, really—over the course of time, across various locations and periods of someone's life. Sometimes I have my friends hold onto drawings or pieces of paper that I haven't drawn onto yet. But when I carry them with me, I take them out, unfold them, look at them for a while, I hang them on the wall, and then I refold them back up before moving them somewhere else. They're like keepsakes or talismans, kind of. Or maybe curses, depending on the drawing [laughs]. But every time they get folded, that history—that time that I spent with them—it gets permanently recorded on their surfaces.

LX: Do you want the eventual owner of the work to be able to carry it in their pocket, the way someone might keep a photo of a loved one in a wallet? Is that a way of keeping it “close to home”?

ZTN: If they buy it unframed, I usually tell collectors that they can do as they wish with the drawings. The folding and carrying is part of the creation of the work, which has the potential to continue for as long as I have possession of it. But once someone buys an unframed work, they can choose to continue that process or keep it as it is. But I like that idea of folding and portability as having some kind of relation to “home.” Come to think of it, maybe I should add that to my answer to your first question [laughs]! So, “home” for me is also what we carry with us across time and geographies, the things that continuously witness our changes and transformations. I guess the idea of “home" being decidedly separate from a geographic location makes real sense, too, in the context of my practice and family history. The folded sheet of paper, for me, evokes documents—especially refugee documents like the asylum forms or identification papers that my parents and grandparents might’ve carried with them. I'm interested in the fold as indicative of something that’s necessary to hold onto for safekeeping, yet at the same time it's not precious or holy enough to preserve in perfect condition. That’s where the folds in my drawings come from, really: thinking about putting away an important document and taking it back out as needed, over and over and over and over. Most of the drawings are even built from document-sized sheets, like I'm working with the materiality of the immigration system itself.

The folded sheet of paper, for me, evokes documents—especially refugee documents like the asylum forms or identification papers that my parents and grandparents might’ve carried with them […] That’s where the folds in my drawings come from, really: thinking about putting away an important document and taking it back out as needed, over and over and over and over.

LX: The fact that one paper could be indicative of if someone’s a citizen of a place or not is still conceptually insane to me, even on a humanity front.

ZTN: Yeah, like somebody's humanity and value being reduced down to nothing more than an 8.5 x 11. It really is a violent thing to classify people into categories and bits of data that determine their livelihood, their health, safety, and where they can live. At the same time, though, the sheet of paper is also used for a plethora of other purposes that might not be associated with violence at all! Like, love letters and recipes and books. So the real culprit here, I think, is standardization and the things that come with it: regulation, bureaucracy, and control.

LX: Tell me about Starlit.

Figure 6: Z.T. Nguyễn, Starlit, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 40.5 x 32 inches (102.87 x 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the art and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

ZTN: So this piece is probably the start of the transition from my earlier work at Yale—which makes up most of what we've already talked about so far—to where my ideas are at now. It consists of a few motifs we've already discussed: folded paper, a five-pointed star, and an Asian American moon moth—specifically, a Pink Spirit Moth, which is indigenous to Laos and Vietnam. What's newer here is the pocket knife, which is based on the one my father carries, the severed head, and heavily saturated color. The head might be related to the cropped bodies we talked about towards the beginning, but I think it's really its own thing. When I draw heads without bodies, they aren't necessarily dead or decapitated, since I imagine them still capable of seeing, hearing, thinking, and speaking, but incapable of moving. That tension, that powerlessness or helplessness, definitely has political origins for me.

I made Starlit during the summer of 2024, following a peak in widespread student-led political movements on campus during my time at Yale, which was met with police violence and aggressive retaliation from the university's administration. The same was happening on university campuses across the US and throughout the world. I participated in these movements firsthand, helped to organize them, witnessed the university's response in real time, all while seeing multiple genocides that were happening—that are still happening—on social media and press coverage… and it all really profoundly impacted me. These administrative and militarized systems, whether people are working within or directly against them, are just so much bigger than any of us individually. That sense of scale and of being small in the face of something vast—that's what the severed head is to me. It's a political motif. The knife, too, with its sharpness and inherent danger as a weapon, is kind of like the mosquito and tied to precarity. But what I don't want for this work is for it to defend inaction. I think, if anything, making this work encouraged me to think more on ways to take action, to seek out collective power because of my powerlessness as an individual. I think of this piece as a snapshot of a particular emotional and political moment that deeply affected me.

The works that I made after Starlit—from that summer until now—share these political influences and lean more into the nocturnal or nighttime theme I mentioned earlier in our conversation. A number of these works ended up becoming my thesis at Yale, and most were included in my first solo show, Facts Are Bigger in the Dark, which was shown at island this past summer, which is a gallery in New York's Chinatown.

Figure 7: Z.T. Nguyễn, Cat and Mosquitoes, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 40.5 x 32 inches (102.87 x 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: How did the show's nocturnal theme relate to politics?

ZTN: I think it's metaphorical or allegorical for revolutionary potential, but I'm not always interested in depicting that explicitly in my work; I'm more interested in harnessing what that potential feels like, and what inspires it. I started describing the night as a way of exploring the psychological space between stasis and change. Even if the works don’t look like night, they all live there in that transitional space. The darkness of night makes it hard to see clearly, and that demands different ways of moving through the world. That's why a lot of the animals that appear in my work are nocturnal—from moths and mosquitoes to cats. I almost always choose animals based on what helps them to navigate the night and survive. Moths have powdered wing textures that can make their flight silent and disrupt a bat's echolocation. For cats, it's their nocturnal vision and stalking. But since human figures were the real anchor of the show, sometimes they even took on these qualities to make it through the night, like a person who could turn their head all the way around like an owl. I'm really interested in human activities that happen regularly, or even exclusively, under the cover of the night’s darkness: parties, sex, drugs, crime, but also dissent, resistance, escape, and even witchcraft or communication with demons and spirits. I think witches are revolutionary beings. I haven't referenced witchcraft directly in my work, since I'm unfortunately not a witch myself, but I find them fascinating. On the other hand, I do have experiences with ghosts, and so does my family.

Figure 8: Z.T. Nguyễn, Neck, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 26 x 130 inches (66.04 x 330.2 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: Is your family superstitious?

ZTN: A bit, yes. We definitely believe in ghosts, at the very least. My parents and I were just talking about this last night, actually, and sharing ghost stories, bringing up people we know who are true mediums. I personally am not a medium by any means, but when I lived in Providence as an undergrad at RISD, I definitely had my fair share of ghost encounters. We also talked a bit about bùa ngải, which is a type of evil sorcery in Vietnam that involves curses, blood rituals, and mind control.

I'm really interested in human activities that happen regularly, or even exclusively, under the cover of the night’s darkness: parties, sex, drugs, crime, but also dissent, resistance, escape, and even witchcraft or communication with demons and spirits.

LX: Why did you choose to anchor the body and why did you choose these particular hues for your show?

ZTN: I think the body felt pretty natural of a choice for me. I talked about it a bit towards the beginning of our conversation, but most of the bodies I draw are my own. They're depictions of my physical sensations that come from experiences of otherness, which have largely informed my political engagements and interests. My colors, on the other hand, were chosen based on their proximity to or their distance from the color red. I was reading Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red and Eros the Bittersweet while making a lot of this work. The latter uses examples of Sappho’s poetry to explain that desire requires a space, a distance, between the desirer and the desired in order to exist. That space is comparable to the nighttime for me, because it’s a liminal zone between stasis and change. I started associating that space with red, thanks to Autobiography of Red, but also because of forces like lust, anger, or ecstasy which feel both like the color red and frustratingly liminal to me. When I chose colors for the drawings that eventually were included in the show, it was always about their relationship to red, to that emotional space. Purple and indigo felt like a few steps away from it; orange was closer, but standing on edge nearby; and pink was a muted, softer version of it, nestled beside it. Every color choice could be traced back to red as the emotional origin.

Figure 9: Z.T. Nguyễn, Insectoid, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 32 x 32 inches (81.28 x 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: What is the CRT in Watching about?

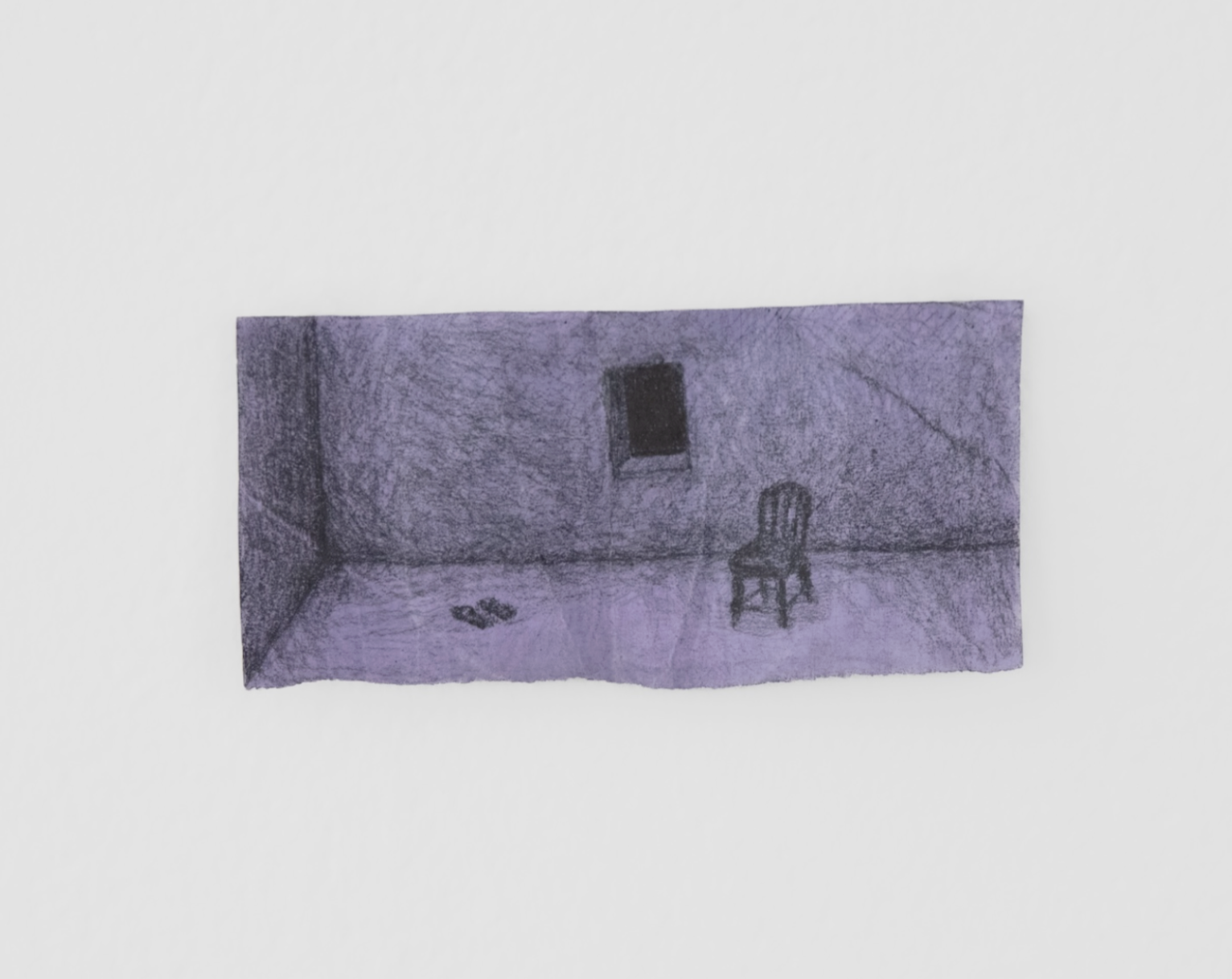

Figure 10: Z.T. Nguyễn, Watching, hand-drawn digital image, found CRT television, acrylic-pigmented cement, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy the artist and island © Z.T. Nguyễn and island

ZTN: I grew up with CRT TV sets, so I think it evokes a sense of domesticity, like it's a snapshot of the home at night. But it isn't necessarily a warm or welcoming home space, which I think is felt though the cement pill bottles and beer bottles and that garish magenta color, but also in the other furniture piece in the show, which is a chair that's flipped over with a drawing hanging on its underside. I’d been wanting to use the backsides and undersides of discarded furniture pieces as unconventional frames for my drawings, since they're the parts of the furniture that you're not supposed to see, which affects the conceptual context for viewing the drawings. Like, is this drawing a secret that I'm only seeing because someone happened to flip this chair over? And why did they flip it over? Was it in a fit of rage? I ended up naming the chair piece after the show, Facts Are Bigger in the Dark. Eventually, one day, I’d really love to do a show where all the drawings are displayed on the backs or on the undersides of furniture, and none are on the walls.

Figure 11: Z.T. Nguyễn, Facts Are Bigger in the Dark, squid ink, graphite, colored pencil, and acrylic on letter-sized sheet of paper; overturned found chair, 23.5 x 36 x 16 inches (59.69 x 91.44 x 40.64 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

But the drawing itself for this piece was made with squid ink, actually, which I feel was a significant choice for me. Fun fact: squid ink is actually the original sepia ink! I guess it's no longer a standard art material, though, because I had to get it from a culinary website, since it's more commonly used to dye food in Italian and Japanese cuisines. I really wanted to make a drawing using the materiality of fear. And since squids and octopuses and cuttlefish emit ink to escape danger, it was kinda perfect. It smells really, really bad, though—like, super fishy—[laughs] and it's a really difficult material to work with, so the drippy, messy markmaking just emerged as I drew it. Graphite is such a controlled medium in comparison, especially because I mostly use mechanical pencils, so it was a bit of a challenge for me to get it to look decent. It even works differently than other kinds of ink, like India ink—it just sits on top of the paper and doesn't absorb into it as easily.

LX: That makes sense that it’d be viscous. But there’s also something about the ink itself, as a kind of self-protective mechanism. Even with squid, it’s about defense, survival.

ZTN: Right, like that's part of its defense; it even resists my control over it. I had to learn to let go of my sense of control and ended up just spraying it with water so it could just drip all around the paper. And that ended up working really well! It was so much better when I let it do its own thing; it actually looked like the materiality of fear.

LX: When I saw the CRT TV and single chair, I subconsciously thought of Warhol’s Electric Chair. Was that your intention, or were you more focused on evoking absence?

Figure 12: Andy Warhol, Electric Chair, 1971, screenprint, sheet: 35 7/16 x 47 ⅞ inches (90 x 121.6 cm). Edition 192/250 | 50 APs. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Peter M. Brant © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (73.92.3) https://whitney.org/collection/works/7335

ZTN: It wasn't my intention, but I'm glad you thought of that because of its political indications. I personally was more focused on absence and a kind of unfriendly domestic space, which I mentioned earlier with Watching. But I think it's best exemplified in the smallest drawing in the show, which is less than two inches on its shortest side. Its title is Home, and I think the significance of its impact is in its small size versus some of the bodies in other drawings around it that are larger than life. So, what does it mean for this space—this home, this place of supposed comfort and rest—to be so tiny that a body could never fit into it? What does someone do when their own home is too small for them?

Figure 13: Z.T. Nguyễn, Home, graphite and acrylic on paper, 3.9 x 1.9 inches (9.90 x 4.82 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: Did you ever feel that way while making this, like physically out of place or out of sync? I’m thinking about how our bodies sometimes feel out of space, and whether that influenced the scale of your work.

ZTN: I think so. Those feelings, for me, come from being queer, being Southeast Asian, ongoing politics, all of the things we've been talking about so far. Not belonging and not being heard. Interestingly, for a work that has so much of my personal strife wrapped up into its ideation, I think it’s the smallest finished artwork I've ever made. I wonder what that means [laughs].

Figure 14: Z.T. Nguyễn, Almost, graphite, colored pencil, soft pastel, and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 172 x 32.5 inches (436.88 x 82.55 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyen

LXM: Fascinating, tell me more about Almost.

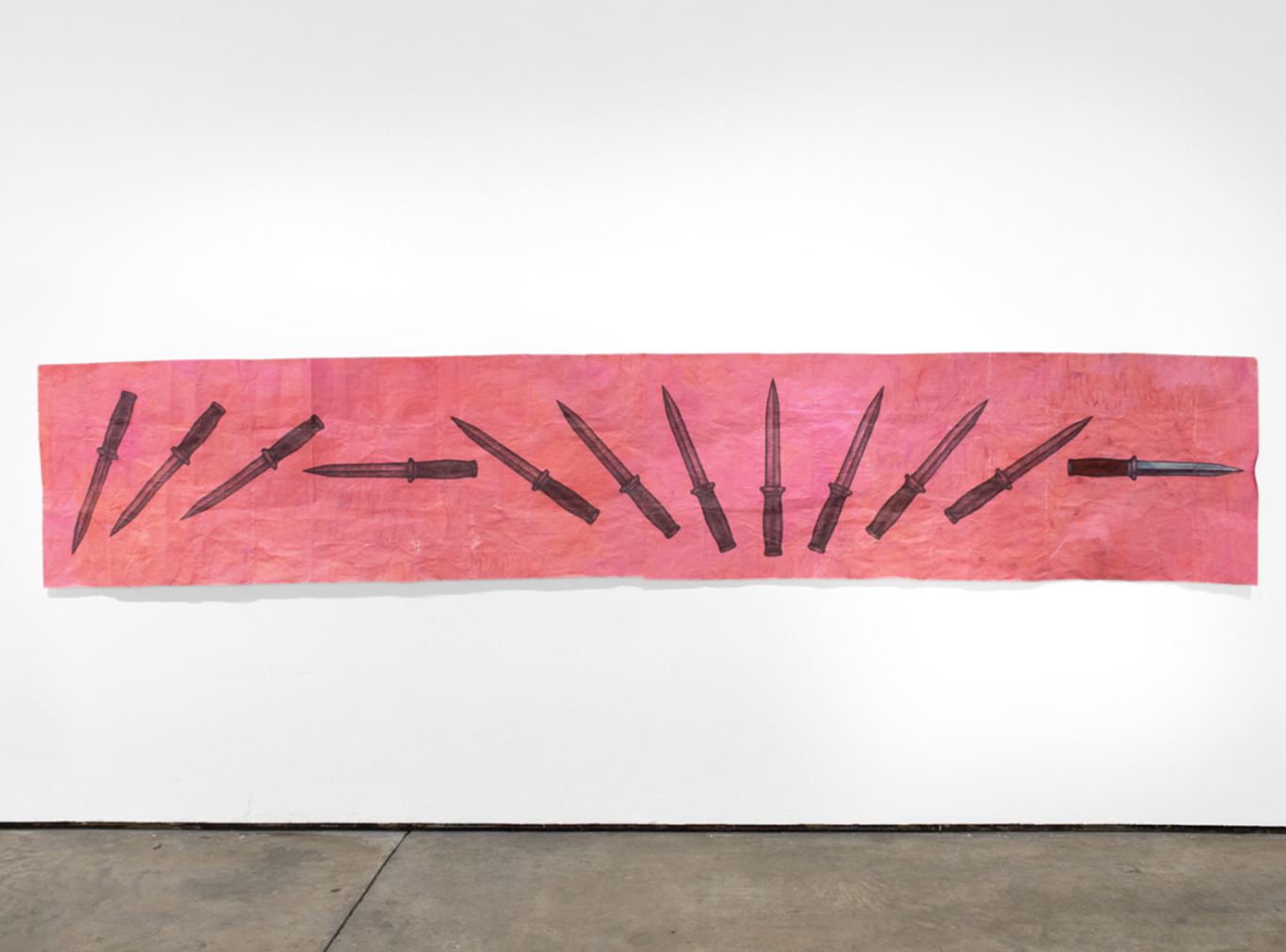

ZTN: Funny that we're following the smallest work in the show with this piece, which I think might be the largest. I had to watch a lot of slow-motion videos of knife throwers to make this drawing; I was studying how knives spin through the air, so that the drawing could imply that same movement. The process of drawing the same knife over and over again as it spins through space was really tedious and time-consuming, but I consider that to be part of the potential energy of the drawing and the effect it has on a viewer. The whole thing is about fourteen-and-a-half feet long—the longest single dimension out of all the works in the show—but it all comes down to the moment where the rightmost edge puckers inwards to meet the tip of the rightmost knife: the only one in the drawing that's fully rendered in color with soft pastel. That edge shifts into a deeper magenta or red, almost like it's bruising as it strains itself to meet the blade, like it's asking to be punctured. It’s about that split second before it hits—that tiny space between the tip of the knife and the edge of the paper.

LX: I love that undulating edge. Is it meant to suggest puncturing skin or a specific body part?

Figure 15: Z.T. Nguyễn, Almost (detail), graphite, colored pencil, soft pastel, and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 172 x 32.5 inches (436.88 x 82.55 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyen

ZTN: Not necessarily, but I'm not opposed to that interpretation at all. I wanted the pink to feel bodily, but not strictly skin-like. More like the layers beneath the skin's surface—something flesh-like, almost like the color of muscular diagrams in science or anatomy textbooks, but maybe more vibrant or urgent than that. Similarly to how I was talking about color before, this pink is also about its relationship to red: it's a softer, less powerful version of it. Like, think of this pink as the potential energy of anticipation, and the red edge as the intensity of rupture. In a lot of ways, I think this work was the centerpiece of the whole show, even though I also think it's the most different from the rest of the works… it's like this one piece summarizes the emotional qualities that the others achieve collectively.

LX: Fascinating. Before we end, let's move on to your Perrotin work and its text.

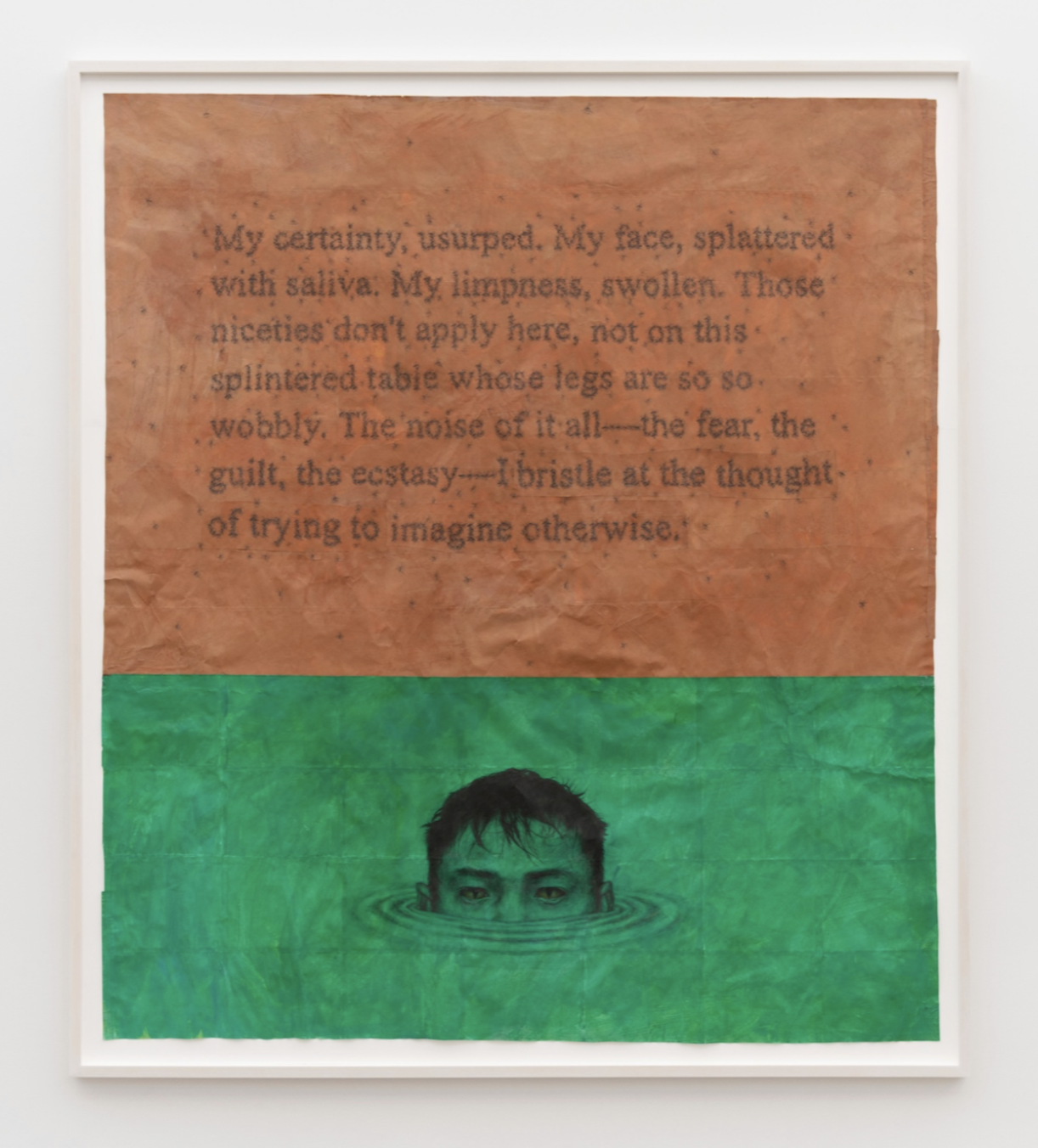

ZTN: Ah, yes. This one is my baby [laughs]! Or, like my big baby. They’re all my babies, but I think I'm still really attached to this one because it was the last piece that I made at Yale. I wrote the text for it myself, but originally it was for this creative writing class that I was lucky enough to have taken in my last semester. It was a prose poem I wrote for an assignment, but I figured it could actually work really well as a drawing. Let me read it to you:

My certainty, usurped. My face, splattered with saliva. My limpness, swollen. Those niceties don't apply here, not on this splintered table whose legs are so so wobbly. The noise of it all—the fear, the guilt, the ecstasy—I bristle at the thought of trying to imagine it otherwise.

It took a massive effort on my part to draw the mosquito-text, which I did over the course of a few days. I think I must’ve pulled two at least all-nighters to get it done before my last final critique at Yale? I was also preparing for surgery during that time so I was in a lot of physical pain and discomfort, which had been going on for, like, two months at that point. It was a brutal last semester; I don't know why I did all that [laughs]. But I'm kinda glad it all worked out, since I'm actually really pleased with the result. I kept thinking about how fragile, how impossible it would be for mosquitoes to come together to spell words that have meaning like this. But also, if it actually happened, I thought about how painstakingly brief it would last before dissolving. Kinda like Mosquito Star, which we discussed earlier, but on a much more ambitious scale.

LX: Wait, so the writing is actually tiny drawings of mosquitoes?

ZTN: Yeah! The words are made up of about 2,500 individually-drawn mosquitoes. I think I'm really interested in the meaning of the words, of the language, but within the context of the mosquitoes. Like, yes, it is about the homoerotic and masochistic implications of the words themselves, but, it's contained by the brevity of a moment when everything suddenly aligns and becomes clear, only for it to scatter away from you. Like, how precarious and fragile and fleeting a split second of clarity can be, and the desire that you have to hold onto it, or to stretch it out. That's what this drawing is. I see that in the lower green portion, too, with the head rising from the water, but I think a lot of its significance does lie in the upper brown portion, in the mosquito-text. I wrote about it in an Instagram post, which articulates it a bit better than how I'm explaining it right now, I think. I can read it for you:

The words in A sort of delicious terror are made up of roughly 2,500 individually hand-drawn mosquitoes in flight—a swarm that some might describe as precarious, or maybe even threatening. It's a motif I've invoked several times in the past few years of drawing.

But I think I'm (slightly) less interested in the precarity of the mosquitoes themselves here, and more interested in the precarity of so many moving parts. If mosquitoes ever actually converged to form language like this, any kind of meaning that's conveyed would be so brief it would only last an instant—and then in the next, the mosquitoes would dissipate back into chaos. This drawing is largely about holding that instant, the moment where things align against all odds before falling apart again. It's about how we remind ourselves of the moments that are profoundly meaningful and erotic and liberating and humbling and radical and necessary, especially amidst genocide, fear-mongering, and violence. If there's one thing I’ve had to do the most during my MFA at Yale, it was maintaining and tending to these moments continuously alongside engagement and action as times and circumstances changed and warped.